Most of the nitrogen and phosphorus in factory farm manure enters the environment, causing myriad problems in air, water, and soil. The dispersal of these manure nutrients (once highly valued) is one of the central negative externalities of industrial animal ag. Quantifying the amounts is an important step in understanding the scope of the problem.

Nutrients from manure enter waterways causing eutrophication, one of the most pressing environmental problems.[1] Nitrogen from manure also volatizes into ammonia, transforming into PM2.5 and other air-polluting compounds.[2]

For decades federal agencies have been unable to stop factory farms from using an array of manure dispersal techniques.[3,4] Current agency reports tend to obscure the fact that most manure nutrients from factory farms are damaging the environment, with very small shares fertilizing crops.[5]

U.S. EPA (2023) Nutrient Pollution, https://www.epa.gov/nutrientpollution [“Nutrient water pollution is one of the most widespread and challenging environmental problems faced by our nation.”]

For details regarding manure, ammonia emissions, and PM2.5 see, Nitrogen and Air Quality and Animal Ag Ammonia & PM2.5

U.S. EPA (2023) Mississippi River/Gulf of Mexico Watershed Nutrient Task Force 2023 Report to Congress, Fourth Report, p. 2. [“In 2001, the HTF first agreed to meet a coastal goal of reducing the size of the hypoxic zone in the northern Gulf to a 5-year annual average of less than 5,000 square kilometers (1,930 square miles) by 2015, subject to the availability of resources.” According to the NOAA, the dead zone is estimated at 6,705 square miles in 2024. Factory farm manure plays a major role in the dead zone, though “manure” is mentioned 4 times in this 159 page report.]

Ribaudo, M., et al., (2017). The potential role for a nitrogen compliance policy in mitigating Gulf hypoxia. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 39(3), 458-478. [“Farms specializing in livestock appear to contribute a disproportionate share of excess nitrogen applications.”]

Lim, T., et al., (2023) Increasing the Value of Animal Manure for Farmers, USDA Economic Research Service, AP-109, Table 2, Figure 4. [Only a very careful reading of this 94-page report would clarify that: the factory farm system is creating massive amounts of unusable manure, most nitrogen and large portions of phosphorus are lost well before land application, factory farmers land-apply manure as a way to rid themselves of a liability (not to fertilize crops), a large percentage of farmers admit to applying full shares of chemical fertilizer along with manure, very small shares of total nitrogen in manure are being land-applied, and most of what is applied uses methods that do not incorporate nutrients into the soil. Although the effort to help farmers find more value in manure is commendable, the factory farming system along with weak regulations have so far proven to be insurmountable barriers to unlocking that value.]

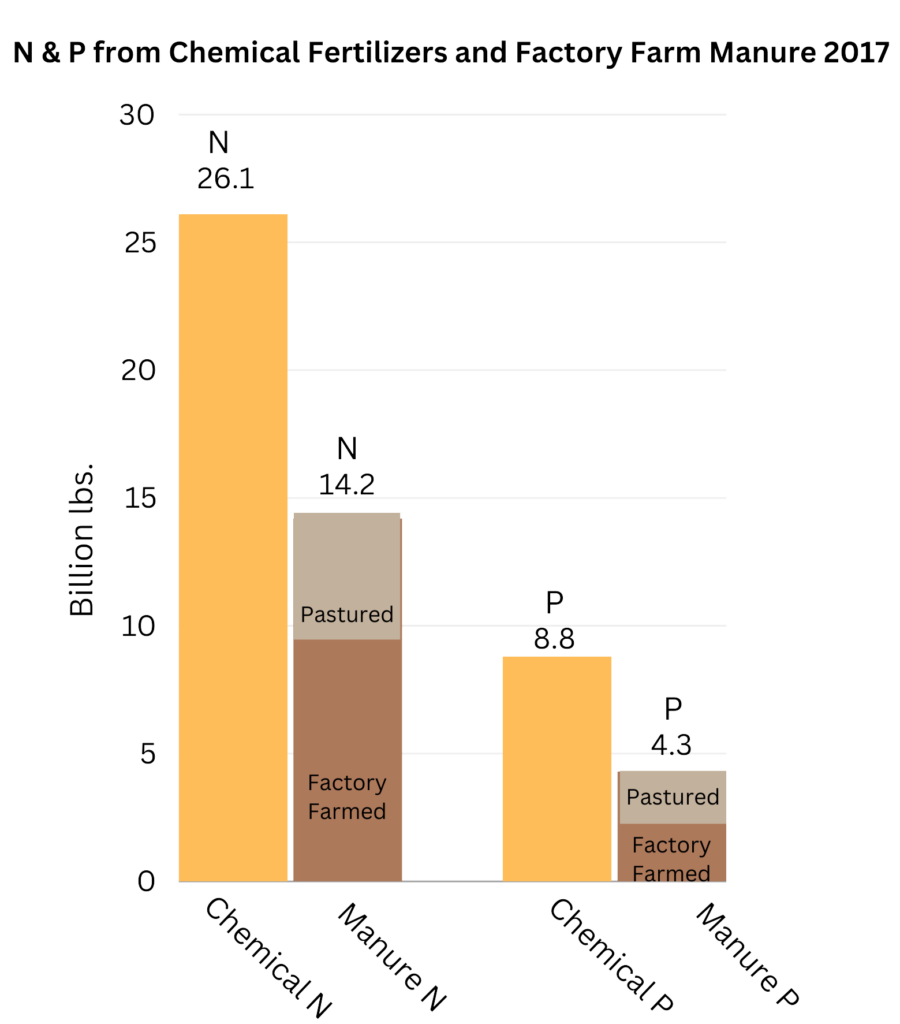

About 14 billion pounds of nitrogen and 4 billion pounds of phosphorus were excreted in farmed animal manure in 2017.[1-3]

U.S. EPA (2023) Estimated Animal Agriculture Nitrogen and Phosphorus from Manure

https://www.epa.gov/nutrientpollution/estimated-animal-agriculture-nitrogen-and-phosphorus-manure [2017 totals: 14,201,994,389 pounds of N, and 4,294,399,611 pounds of P. State figures are totaled for cattle, swine, poultry (chickens and turkeys), sheep, and horses.]Gollehon, N. R., et al., (2016). Estimates of recoverable and non-recoverable manure nutrients based on the census of agriculture—2012 results. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Services, Washington, DC, tables 3&4, p. 10. [2012 totals: (N) 16,167,734,000 and (P) 4,527,395,000. These USDA figures also include goats, bison, ducks, and many other poultry and “specialty livestock” species. Horses from operations defined as farms are included.]

Note: we use these EPA estimates for 2017 as most credible, while acknowledging other sources: a) Bian, Z., et al., (2021). Production and application of manure nitrogen and phosphorus in the United States since 1860. Earth System Science Data, 13(2), 515-527. [Estimates total manure N at ~16.3 billion pounds (7.4 teragrams) and ~5.1 billion pounds of P (2.3 teragrams.] b) FAOSTAT, Land Inputs and Sustainability/ Livestock Manure/ Amount excreted in manure (N content)/ 2022. [Estimates total N manure in the U.S at ~13.1 billion pounds for 9 types of farmed animals.]

The ratio of total nitrogen volume in chemical fertilizers to total nitrogen in farmed animal manure is about 2 to 1. It’s also about 2 to 1 for phosphorus.

Nitrogen volume in manure is equal to ~54% of the total nitrogen in chemical fertilizers.[1] Phosphorus in manure is equal to ~49% of phosphorus in chemical fertilizers.[2]

U.S. EPA (2023) Commercial Fertilizer Purchased. https://www.epa.gov/nutrientpollution/commercial-fertilizer-purchased#table1 [State totals were added to reach figures for 2017: 26,062,016,614 lbs. of nitrogen and 8,761,934,424 lbs. of phosphorus. Calculations as follows: For N, 14,201,994,389 / 26,062,016,614 = 54.49% (54%). For P, 4,294,399,611 / 8,761,934,424 == 49.01% (49%)]

About 64% of the nitrogen and 48% of the phosphorus in total animal manure is from confined animals on AFOs. Conversely, ~36% of nitrogen from all farmed animals is released on pasture, along with ~52% of phosphorus. These were the estimated percentages in 2012.[1]

The total volume of nitrogen from factory farms is ~35% of the volume of nitrogen from chemical fertilizers. The total volume of phosphorus is ~24% of the volume from chemical fertilizers.[2]

These figures should be viewed as broad estimates. The increasing consolidation of animals has likely led to a greater share of manure on factory farms, though farmed animal diets have changed, possibly leading to overall reductions in the levels of excreted nutrients.[3] Also, the estimates are based on figures from different years.

Gollehon, N. R., et al., (2016). Estimates of recoverable and non-recoverable manure nutrients based on the census of agriculture—2012 results, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Services, Washington, DC, tables 3 & 4, p. 10 [Total nitrogen from AFOs equals 63.5% of nitrogen from all farmed animals. Total phosphorus from AFOs equals 48.3% of phosphorus from all farmed animals. We apply these 2012 percentages to 2017 EPA data on total nutrients from animal manure. For (N) .64 * 14.20 = 9.1. For (P) 4.29 * .48 = 2.1]

Calculations: 9.1 / 26.1 = 34.9%. 2.1 / 8.8 = 23.9%.

Kleinman, P.J.A., et al., (2019) Managing Animal Manure to Minimize Phosphorus Losses from Land to Water, Animal Manure: Production, Characteristics, Environmental Concerns and Management, Waldrip, H.M. et al., (eds.) American Society of Agronomy, Special Publication 67, Madison, WI, pp. 207-208.

According to a group of experts including USDA scientists, “No sector in agriculture has been more closely tied to the accelerated eutrophication of aquatic systems than animal agriculture, principally as a result of the generation and management of manure.”[1]

In a 2021 USGS study, manure was identified as the number one source of nitrogen (29% of the total) in watersheds covering all or parts of 31 agricultural states throughout the Midwest. This was more than chemical fertilizers. Manure contributed just less than a quarter (24%) of anthropogenic sources of phosphorus – about half as much as chemical fertilizers.[2] Large amounts of nitrogen are escaping from manure through volatilization into ammonia, causing major air quality damages and eventually through deposition creating additional damage to terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems.[3]

In general, information from federal agencies is limited regarding the relative share of pollution from chemical fertilizers and manure and the routes by which they are entering the environment.[4]

This is despite the EPA’s acknowledgement that nutrient pollution has “profound implications for public health, water quality, and the economy.”[5]

Kleinman, P.J.A., et al., (2019) Managing Animal Manure to Minimize Phosphorus Losses from Land to Water, Animal Manure: Production, Characteristics, Environmental Concerns and Management, Waldrip, H.M. et al., (eds.) American Society of Agronomy, Special Publication 67, Madison, WI, p. 201.

Robertson, D. M., & Saad, D. A. (2021). Nitrogen and phosphorus sources and delivery from the Mississippi/Atchafalaya River basin: An update using 2012 SPARROW models. JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources Association, 57(3), 406-429. Table 2, p. 415; Table 4, p. 420; Figure 5 p. 418. [N = 28.9%. P = 18.2% / 77.3% anthropogenic = 23.5%]

See details regarding manure, ammonia emissions, and impacts on air quality at: Nitrogen and Air Quality and Animal Ag Ammonia & PM2.5

Rosov, K., et al., (2020). Waste nutrients from U.S. animal feeding operations: Regulations are inconsistent across states and inadequately assess nutrient export risk. Journal of Environmental Management, 269, 110738, p. 9. [“Finally, while scientific evidence clearly demonstrates damaging water quality consequences from CAFO waste disposal practices, there are few, if any, quantitative, empirical federal or state sponsored analyses of manure nutrient exports.”]

Radhika Fox (EPA Assistant Administrator) to State Environmental Secretaries, Commissioners, and Directors State Agriculture Secretaries, Commissioners, and Directors Tribal Environmental and Natural Resource Director (April 5, 2022) Memorandum: Accelerating Nutrient Pollution Reductions in the Nation’s Waters, Washington, D.C., p. 1. https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2022-04/accelerating-nutrient-reductions-4-2022.pdf

Nitrogen from factory farm manure starts to volatize into ammonia (NH3) soon after excretion. Perhaps about a third escapes into the environment within hours or days, and losses continue through all stages of manure management.[1] Losses increase dramatically during land application.[2,3]

We are not aware of firm estimates for the overall shares of nitrogen in manure that escape into air (mostly as ammonia) as opposed to water. Emissions vary greatly depending on the type of animal and the manure storage systems.[4,5]

Rotz, C. A. (2004). Management to reduce nitrogen losses in animal production. Journal of animal science, 82 (suppl_13), E119-E137. [“Volatile loss begins soon after excretion, and it continues through all manure handling processes until the manure nutrients are incorporated into soil.” at p. E-120. “Up to half of the excreted nitrogen is lost from the housing facility…” at p. E-119. The broad estimate of one-third loss is our calculation based on figures from Table 2 and assumptions about the most common facilities and manure handling methods. Most nitrogen loss at the facility is in the form of ammonia. See, fn b]

Meisinger, J. J., & Jokela, W. E. (2000). Ammonia volatilization from dairy and poultry manure. Managing nutrients and pathogens from animal agriculture. NRAES-130. Natural Resource, Agriculture, and Engineering Service, Ithaca, NY, 334-354. [Ammonia loss estimates for non-incorporated land-applied dairy and poultry manure in the Northeast between 40-100%. at p. 13, Table 1.] [Note: most manure is broadcast sprayed and not incorporated into the soil. See: Leng, T., et al., (2023) Increasing the Value of Animal Manure for Farmers, USDA Economic Research Service, pp. 19-23 and Figures 9-10.]

Chastain, J. P. (2019). Ammonia volatilization losses during irrigation of liquid animal manure. Sustainability, 11(21), 6168, p. 1. [“Broadcast application of liquid or slurry manure without incorporation can result in ammonia losses ranging from 11% to 70% of applied total ammoniacal nitrogen.”]

Rotz, C. A. (2004), Table 2.

Rotz, A., et al., (2021). Environmental assessment of United States dairy farms. Journal of Cleaner Production, 315, 128153, p. 8. [“Over all (dairy) farms simulated in the U.S., 64% of the emitted reactive N was in the form of NH3.”]

In 2022, manure was applied to ~22 million acres. This is less than 10% of the 237 million acres that received chemical fertilizers.[1]

USDA (2024) 2022 Census of Agriculture, United States Summary and State Data, Vol 1, Part 51, Table 46, p. 52. [22,169,010 acres versus 236,771,914 acres]

A very small portion of the manure generated from factory farming is applied to crops. Additionally, the manure that is applied to those 22 million acres is often applied in addition to the normal and full applications of chemical fertilizers.[1,2]

According to a report by USDA scientists, “Farms with confined animals generally have inadequate cropland to assimilate nutrients produced and are characterized by excess nutrient applications on cropland they control.”[3] The USDA also reports that 78% percent of manure is applied to land controlled by farmed animal producers.[4,5]

Some portion of the total land area that is receiving manure has been converted to cropland by CAFO owners for the express purpose of getting rid of manure. Those land use conversions are often causing environmental degradation.[6]

Given that the N in manure from factory farms is about a third of the N in chemical fertilizers, and P is about a quarter, it is evident that large volumes of nutrients are being dispersed into the environment prior to and/or after land application (through volatilization and runoff).

Lim, T., et al., (2023) Increasing the Value of Animal Manure for Farmers, USDA Economic Research Service, AP-109, p. 12.

Leytem, A., et al., (2021). Cycling Phosphorus and Nitrogen through Cropping Systems in an Intensive Dairy Production Region. Agronomy (Basel), 11(5), 1005, p. 10. [“This suggests that not only are manure nutrients undervalued but they are not likely included in calculating nutrient budgets, which can lead to overapplication of N and P, particularly on fields receiving manure.”]

Ribaudo, M., et al., (2017). The potential role for a nitrogen compliance policy in mitigating Gulf hypoxia. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 39(3), 458-478, p. 12.

Lim, T., et al., (2023) p. 16. [“For all crops, 78 percent of manure is applied to land controlled by the animal producer, 14 percent is purchased by crop farmers from animal farmers, and 8 percent is given for free to other farmers.”]

USDA (August 2018) Nutrient Management Practices on U.S. Dairy Operations, 2014. National Animal Health Monitoring System, Report 4, pp. I and 29-32. [“Overall, 90 percent of (dairy) operations applied manure to land either owned or rented.”]

Miralha, L., et al., (2021). Spatiotemporal land use change and environmental degradation surrounding CAFOs in Michigan and North Carolina. Science of the Total Environment, 800, 149391. [“Lands near CAFOs changed to cropland, likely to meet manure application needs… These land use changes likely drive environmental degradation…” Abstract]

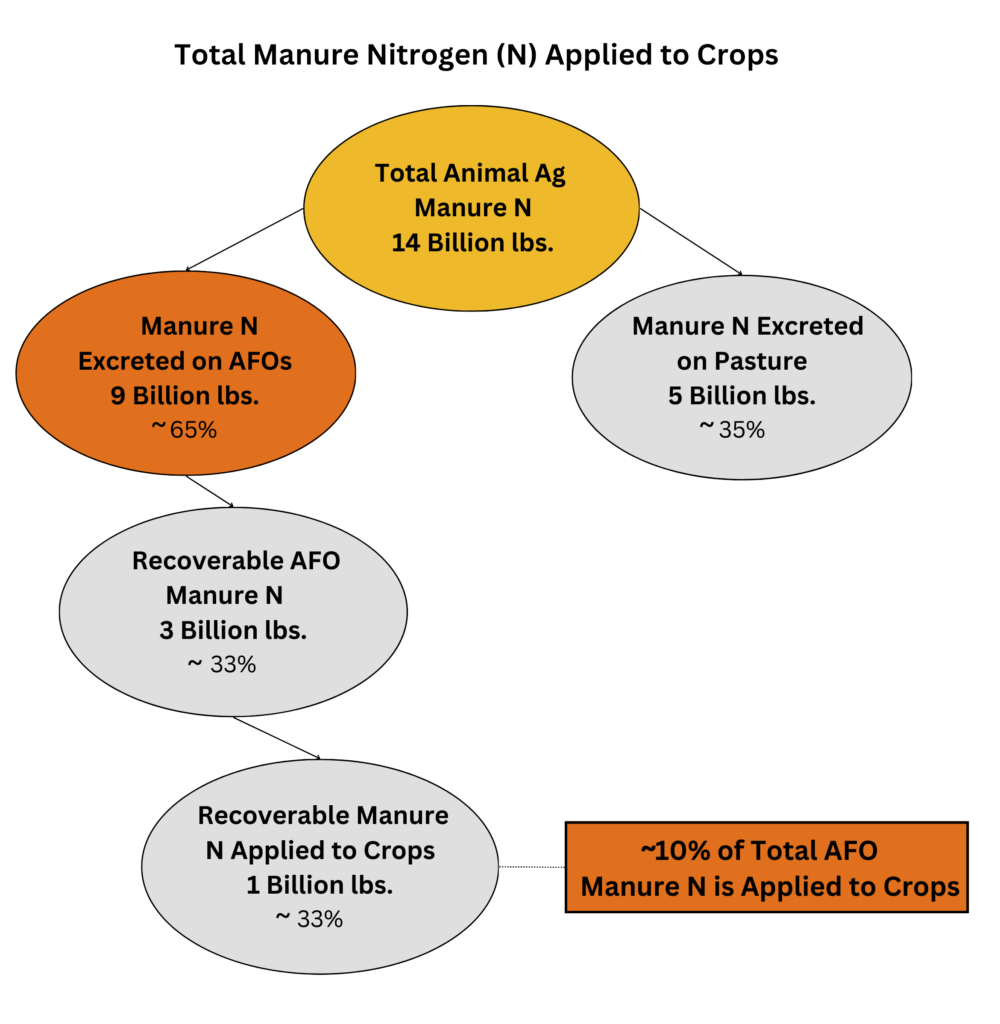

Broadly estimated, about 10% of the total manure nitrogen (N) from factory farms is applied to crops. The great majority of nitrogen in manure escapes into the environment.

Perhaps about a third of the nitrogen in factory farm manure quickly escapes into the environment within hours or days after excretion.[1] After further losses into water, soil, and air during manure storage and transfers, a very small share of nitrogen (N) is eventually applied to crops.

The figures are as follows: The EPA estimates that ~14 billion lbs. of manure nitrogen (N) were generated in 2017 from all animal agriculture.[2]

About 65% or 9 billion lbs. was from factory farms, with the rest generated by animals that were not confined (mostly grazing cattle).[3,4]

Of the 9 billion lbs. of manure nitrogen from factory farms, about one-third is considered “recoverable.” The rest is lost during “collection, transfer, storage, and treatment.”[5]

Of the ~3 billion lbs. recoverable, the USDA estimates that about 1 billion lbs. of manure nitrogen (N) is land-applied to crops.[6]

Of the 1 billion lbs. of land-applied manure nitrogen, perhaps a little more than half is incorporated into crops.[7,8]

In total, broadly estimated, ~10% of manure nitrogen from factory farms is applied to crops.[9,10]

The land application of manure on crops, despite being intensively researched, subsidized, and highly touted, brings very little nitrogen (N) to crops in practice. Almost all the nitrogen from manure from factory farming is entering and damaging ecosystems throughout the country.

Rotz, C. A. (2004). Management to reduce nitrogen losses in animal production. Journal of animal science, 82 (suppl_13), E119-E137, Table 2. [“Up to half of the excreted nitrogen is lost from the housing facility…” The broad estimate of a third is our calculation based on figures from Table 2 and assumptions about the most common facilities and manure handling methods. Most nitrogen loss at the facility is in the form of ammonia. See, fn b]

U.S. EPA (2023) Estimated Animal Agriculture Nitrogen and Phosphorus from Manure. https://www.epa.gov/nutrientpollution/estimated-animal-agriculture-nitrogen-and-phosphorus-manure [2017 totals: 14,201,994,389 pounds of N]

Gollehon, N. R., et al., (2016). Estimates of recoverable and non-recoverable manure nutrients based on the census of agriculture – 2012 results. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Services, Washington, DC, p. 11. [63.5% of manure nitrogen from AFOs (see, Table 3). Calculation: 14.2 billion pounds x .635 = 9.0. In this analysis we equate “factory farming” with Gollehon’s “AFOs” since less than 2% of total manure nitrogen was from “very small AFOs” that might not meet the “factory farm” definition. See Table A-2. All AFOs in this report are defined by “confined animals.”]

Rotz, C. A. (2004). [Notes about a 35% nitrogen loss of N for grazing feces and urine application. Incorporated nitrogen of pasture-raised beef at less than 10%, feedlot beef ~10%, pastured dairy cattle at ~20% (Table 4). Therefore, the overall nitrogen loss from grazing cattle is very high. (p. E121)]

Gollehon, N. R., et al., (2016), p. 11. [“The amount of recoverable manure nitrogen was 34 percent…”]

Lim, T., et al., (2023) Increasing the Value of Animal Manure for Farmers, USDA Economic Research Service, p. 13. [“Corn acres received more than 410,000 tons of manure nitrogen, 81 percent of total applied nitrogen.” 820,000,000 lbs. / .81 = 1.01 billion lbs.]

See, The Manure Problem for the many reasons that manure is over-applied, used on top of full shares of chemical fertilizers, and applied on land owned by factory farm operations as a way to get rid of a waste product.

USDA NRCS (2017) Effects of Conservation Practices on Nitrogen Loss from Farm Fields: A National Assessment Based on the 2003-06 CEAP Survey and APEX Modeling Databases. [“Total nitrogen losses were highest for acres receiving manure. The average annual estimate of total nitrogen loss for acres receiving manure was 56 pounds per acre per year, compared to the average annual amount lost for acres not receiving manure of 32 pounds per acre per year.” (at p. 13) A loss of 56 pounds / average of 117 pounds applied = 48% loss. High loss rates are common because the manure is often applied in addition to the full application of chemical fertilizers.]

Calculation: 1 billion pounds / 9 billion pounds = ~11%. [Of all animal ag manure nitrogen, including manure on pasture, land application is about 7% or 1 billion pounds / 14 billion pounds.] For further information for the reasons such small shares of nitrogen are applied, see, Animal Ag Water Pollution Sources [question: “In what ways does manure lead to nutrient pollution?]

Note that there is some share of manure applied to hay and grassland that is not included in this tally. According to the USDA [Lim, T., et al., (2023) Increasing the Value of Animal Manure for Farmers, USDA Economic Research Service, p. 12. “Hay acreage and grassland also receive manure. USDA data from 2006 shows that 26 percent of manured acres were hay and grass acres.”] Including this amount would change the 1 billion pound estimate to ~1.4 billion lbs. However, grassland is not a crop. And since about half of manure nitrogen is applied in addition to full chemical fertilizer applications, it is clear that much of the total application is simply a form of dispersal rather than effective crop application. See, Lim, p. 12: “only 44 percent of farmers who applied manure to corn also reduced commercial fertilizer applications to corn because of manure applications.” Corn accounts for the great majority of usage.

N and P that is not taken up by plants is generally lost to the environment through various paths:

N and P is often over-applied or incorrectly applied on crops, subject to later runoff into waterways.

Manure can be stored on site, though it is then subject to natural or catastrophic losses via many types of dispersals from manure storage systems.

Large amounts of the nitrogen in manure are volatilized, with some eventually returning to waterways through atmospheric deposition.[1,2]

Phosphorus can settle at the bottom of storage facilities such as lagoons.[3]

N and P can accumulate in soils and reach saturation levels, above which further application leads to runoff.[4]

Animals grazing on pasture also contribute to nitrogen and phosphorus loads in waterways.[5] About a third of the manure nitrogen from grazing animals is lost to the environment, through leaching or volatilization.[6]

Robertson, D. M., & Saad, D. A. (2021). Nitrogen and phosphorus sources and delivery from the Mississippi/Atchafalaya River basin: An update using 2012 SPARROW models. JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources Association, 57(3), 406-429, p. 410.

See details regarding manure, ammonia emissions, and impacts on air quality at: Nitrogen and Air Quality and Animal Ag Ammonia & PM2.5

Lim, T., et al., (2023) Increasing the Value of Animal Manure for Farmers, USDA Economic Research Service, AP-109, p. 13.

Dari, B., et al., (2018). Consistency of the Threshold Phosphorus Saturation Ratio across a Wide Geographic Range of Acid Soils. Agrosystems, Geosciences & Environment, 1(1), 1–8.

Hubbard, R. K., et al., (2004). Water quality and the grazing animal. Journal of Animal Science, 82 E-Suppl, E255–E263.

Rotz, C. A. (2004). Management to reduce nitrogen losses in animal production. Journal of animal science, 82(suppl_13), E119-E137. [notes about a 35% nitrogen loss of N for grazing feces and urine application (Table 4)]