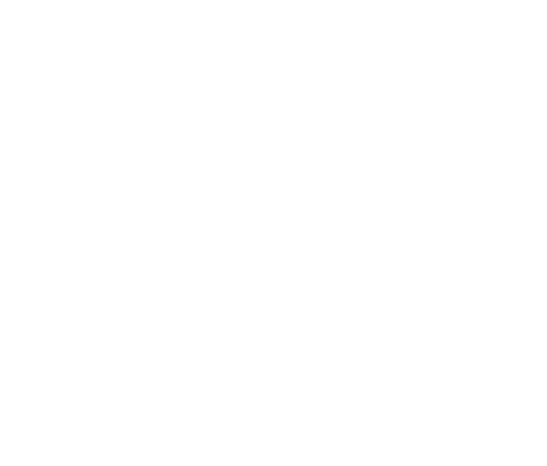

1. Animal agriculture accounts for about 40% of total U.S. water consumption, by far the largest use.

2. It is not commonly understood that this massive use of water has enormous negative impacts on biodiversity, especially on freshwater species.

3. Animal ag water extraction harms freshwater habitats and their myriad species by depleting, diverting, or damming surface waters (lakes, rivers, and streams) and depleting groundwater, including aquifers.

4. As a group, U.S. freshwater species face the highest risks of extinction due to multiple stressors; the central threats are loss of water habitats, changes to water flow, and water pollution.

5. The reduction of groundwater volume harms a wide range of groundwater and surface water ecosystems; approximately half of the water consumed by animal ag is from groundwater and half from surface water.

Broadly estimated, animal ag accounts for about 40% of all U.S. water consumption. The usage is mostly for irrigating feed crops (~38%), with a small share attributed to livestock uses on factory farms (~2%).[1,2]

Note: This is a broad estimate based on 3 reports from experienced water researchers and applying our estimates of the share of crops specifically used for animal feed. For references and calculations, see: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/19XsKhVFbOiyB01Kyz_WVVBdFBa_Pd1JsCISscE7tr08/edit?gid=0#gid=0

See, Feed Crop Water Usage and Water Usage by Factory Farms & Slaughterhouses

The water consumed by animal ag is taken in almost equal parts from surface water – rivers, streams, and lakes – and groundwater, including aquifers.[1]

See, Groundwater & Aquifer Depletion [question: What share of irrigation withdrawals are from surface water versus groundwater?]

Although we reflexively think of water scarcity in human terms, changes to the size or flow of surface waters and groundwaters also diminish the abundance and health of other species.

The depletion and diversion of surface water and groundwater shrinks, fragments, or degrades habitats – the primary threats to freshwater species.

Freshwater species are severely compromised; as a group, they have the highest share of at-risk species in the U.S., facing multiple stressors.[1,2]

As water scarcity for humans intensifies, other species will lose out in the competition for water resources.[3,4]

NatureServe (2023). Biodiversity in Focus: United States Edition. NatureServe: Arlington, VA, p. 11. [“As a group, species associated with fresh water, including amphibians, snails, mussels, crayfish, and many aquatic insects, have the highest percentage of at-risk species, highlighting the importance of conservation strategies to protect freshwater ecosystems.”]

Niederman, T. E., et al., (2025). US Imperiled species and the five drivers of biodiversity loss. BioScience, biaf019. Table 1, p. 5. [93% of imperiled freshwater species impacted by habitat change, 76% by pollution, 65% by climate change.]

Vörösmarty, C. J., et al., (2010). Global threats to human water security and river biodiversity. nature, 467(7315), 555-561, p. 559. [“The situation is even more daunting for biodiversity … global investments are poorly enumerated but likely to be orders of magnitude lower than those for human water security, leaving at risk animal and plant populations, critical habitat and ecosystem services that directly underpin the livelihoods of many of the world’s poor.”]

Dudgeon, D. & Strayer, D. L. (2025). Bending the curve of global freshwater biodiversity loss: what are the prospects? Biological Reviews, 100(1), 205-226, p. 1. [“In many parts of the world, the Anthropocene future seems certain to include extended periods with an absolute scarcity of uncontaminated surface runoff that will inevitably be appropriated by humans.”]

Animal ag’s feed crop irrigation accounts for the largest share of water consumption in the nation.[1] It drains lakes and rivers, dries up wetlands, and empties aquifers. This massive extraction of water is one of the primary threats to aquatic life – the most at-risk subset of species in the nation.

Additionally, the pollution emanating from feed crops and concentrated manure further compromises the remaining water supply, with pollution intensifying as water habitats shrink.[2]

The non-profit NatureServe identifies these 2 factors – water pollution and water management, including dams – as the key threats to U.S. imperiled freshwater species.[3]

The general lack of discussion of the impacts of animal ag’s water usage is likely due to agricultural exceptionalism, an overall lack of interest in biodiversity (especially freshwater biodiversity), and the view that high levels of meat consumption are a necessity.[4]

See, Feed Crop Water Usage

See, Animal Ag’s Contributions to Water Pollution

NatureServe (2023). Biodiversity in Focus: United States Edition. NatureServe: Arlington, VA, Figure 6, p. 16.

Albert, J. S., et al., (2021). Scientists’ warning to humanity on the freshwater biodiversity crisis. Ambio, 50(1), 85-94, p. 88 & 90. [Note: This scientists’ plea to save freshwater biodiversity acknowledges the central role of animal agriculture: “An unsustainable amount of freshwater is used to produce animal livestock.” And yet, of the numerous recommended actions there is just one mention about “implementing conservation agriculture policies that increase the proportion of plant products relative to animal products in human food production chains…”]

Freshwater species are particularly threatened – U.S. freshwater species have the highest percentage of at-risk species due to habitat changes and water pollution.[1,2] “Nowhere is the biodiversity crisis more acute than in freshwater ecosystems. Covering less than 1% of Earth’s surface, these habitats host approximately one-third of vertebrate species and 10% of all species…”[3]

Freshwater species are valuable – Freshwater ecosystems supply and purify almost all the fresh water consumed by humans, they mitigate effects of floods and drought, provide food for other species, and help regulate climate.[4,5]

Freshwater species are neglected – In public perception, the loss of freshwater biodiversity has taken a back seat to threats facing marine or terrestrial species.[6] There is likely a substantial “extinction debt” due to anthropogenic activities with overlooked consequences.[7]

Freshwater species face multiple stressors – Freshwater species are threatened by habitat loss and degradation, pollution, climate change, and invasive species, along with newly emerging threats.[8,9]

With so much at stake and given the outsize impact of feed crop production on water scarcity and pollution, more attention should be paid to industrialized animal ag’s contribution to freshwater biodiversity loss.

NatureServe (2023). Biodiversity in Focus: United States Edition. NatureServe: Arlington, VA, p. 11 and Figure 6, p. 16. [“As a group, species associated with fresh water, including amphibians, snails, mussels, crayfish, and many aquatic insects, have the highest percentage of at-risk species, highlighting the importance of conservation strategies to protect freshwater ecosystems.”]

Vardakas, L., et al., (2025). Global Patterns and Drivers of Freshwater Fish Extinctions: Can We Learn From Our Losses? Global Change Biology, 31(5), e70244. Figure 2, p. 6 and abstract. [“Extinction rates, when calculated per continent using the number of extinct species and the total number of species per continent, indicated that North America has the highest extinction rate.”]

Tickner, D., et al., (2020). Bending the Curve of Global Freshwater Biodiversity Loss: An Emergency Recovery Plan. BioScience, 70(4), 330–342, p. 330.

Lynch, A. J., et al., (2023). People need freshwater biodiversity. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Water, 10(3), e1633. [“Here, we catalog nine fundamental ecosystem services that the biotic components of indigenous freshwater biodiversity provide to people, organized into three categories: material (food; health and genetic resources; material goods), nonmaterial (culture; education and science; recreation), and regulating (catchment integrity; climate regulation; water purification and nutrient cycling).”]

United Nations, UN Water Facts (2024) Water and Ecosystems. https://www.unwater.org/water-facts/water-and-ecosystems

Cooke, S. J., et al., (2013). Failure to engage the public in issues related to inland fishes and fisheries: strategies for building public and political will to promote meaningful conservation. Journal of Fish biology, 83(4), 997-1018, p. 1012. [“Further, the public are not as engaged in freshwater issues compared with the marine realm or with large mammal and bird conservation issues as shown by the results of the present web searches on media inquiries.”]

Dudgeon, D. (2010). Prospects for sustaining freshwater biodiversity in the 21st century: linking ecosystem structure and function. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 2(5–6), 422–430, p. 423. [“In addition, there remains an unquantified but probably substantial, extinction debt due to anthropogenic activities with consequences that have yet to play out completely and declines that occurred in the past which have been overlooked.”]

Dudgeon, D. (2010), p. 424 [“Biodiversity in freshwater ecosystems is under grave threat from human activities, due to the combined effects of multiple stressors such as pollution and habitat degradation, flow regulation, overfishing, and alien species.”]

Reid, A. J., et al., (2019). Emerging threats and persistent conservation challenges for freshwater biodiversity. Biological reviews, 94(3), 849-873.

The 4 major mechanisms:[1]

See the following questions for details.

Aquatic species have evolved in response to the natural flow of rivers and streams. The “complex interaction between flows and physical habitat is a major determinant of the distribution, abundance, and diversity of stream and river organisms.”[1] Predictably, altering the flows of water in rivers and streams has a negative impact on species and their ecosystems.[2]

Feed crop impacts on river flow – A large group of water researchers found that “summer flow depletion (from all sources) is partially responsible for nearly 1,000 instances of increased risk of local extinction of fish species from watersheds in the western US. Of these, 690 (70%) are estimated to have occurred primarily due to irrigation of cattle-feed crops.”[3] The report further concluded that “cattle-feed irrigation is the leading driver of flow depletion in one-third of all western US sub-watersheds; cattle feed irrigation accounts for an average of 75% of all consumptive use in these 369 sub-watersheds.”[4]

River flow depletion effects on lakes – In turn, when rivers that feed lakes are depleted, the water levels of lakes and wetlands recede. One example is the Great Salt Lake which “plays a pivotal role in sustaining biodiversity across western North America through its large, interconnected wetlands.”[5] A recent study found that cattle-feed crops (alfalfa/hay) accounted for 57% of all anthropogenic depletions.[6]

River flow depletion effects on wetlands– River flow depletion due to irrigation reduces the size and health of wetland ecosystems.[7] The loss of wetlands is a central driver of biodiversity loss.[8,9]

Bunn, S. E. & Arthington, A. H. (2002). Basic principles and ecological consequences of altered flow regimes for aquatic biodiversity. Environmental Management, 30(4), 492–507, 493-494.

Poff, N. L. & Zimmerman, J. K. H. (2010). Ecological responses to altered flow regimes: a literature review to inform the science and management of environmental flows. Freshwater Biology, 55(1), 194–205, p. 201. [“As expected, our qualitative analyses clearly demonstrated the many ecological consequences of flow alteration. Of the 165 papers reviewed, 152 (92%) of them reported negative ecological changes in response to a variety of types of flow alteration.”]

Richter, B. D., et al., (2020). Water scarcity and fish imperilment driven by beef production. Nature Sustainability, 3(4), 319–328, table 1, p. 320.

Richter, B. D., et al., (2020), p. 320.

Richter, B.D., et al., (2025) Reducing irrigation of livestock feed is essential to saving Great Salt Lake, Environmental Challenges 18:101065, p. 3. [“The lake serves as a crucial nexus within the Pacific Flyway, offering food and habitat to over 10 million migratory birds and nearly 350 bird species. As habitat loss and degradation persist across the western United States, the lake’s diverse wetlands, islands, and open-water areas are increasingly vital for bird survival and biodiversity.”]

Richter, B.D., et al., (2025), p. 5. [“Cattle-feed crops produced in the GSL basin generated an estimated US$162 million in cash receipts in 2021, equivalent to 0.07% of Utah’s GDP in that year.”]

Lemly, A., et al., (2000). Irrigated Agriculture and Wildlife Conservation: Conflict on a Global Scale. Environmental Management (New York), 25(5), 485–512, p. 485. [“Wetlands can be lost due to draining and direct conversion to agricultural land or because water removal from rivers and streams for use in irrigation robs wetlands of their source of water, and they simply dry up.”]

Lang, M.W., et al., (2024). Status and Trends of Wetlands in the Conterminous United States 2009 to 2019. U.S. Department of the Interior; Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C., p. 10. [“Roughly half of the species protected under the U.S. Endangered Species Act are wetland-dependent.”]

Lemly, A., et al., (2000), Abstract & p. 505. [“The demand for water to support irrigated agriculture has led to the demise of wetlands and their associated wildlife for decades.” “Not only does local wildlife suffer, including extinction of highly insular species, but a ripple effect impacts migratory birds literally around the world.”]

Although we usually think of groundwater and aquifer depletion with regards to water availability for human needs, many plant and animal species rely on groundwater for their survival.[1]

Ecosystems that rely on groundwater for some or all of their water needs are collectively referred to as groundwater-dependent ecosystems (GDEs). These GDEs support a wide variety of species, including fish, amphibians, invertebrates, insects, and plants, many of which are particularly vulnerable to extinction.[2] According to one study, ~17% of endangered species in the U.S. rely on groundwater for survival.[3,4]

Regions with a history of irrigation pumping “are likely to have lost many GDEs over the decades since pumping commenced. For example, intensive groundwater pumping in California’s Central Valley has caused ground water levels to drop below the roots of plants and to become disconnected from stream channels, contributing to a landscape with highly fragmented GDEs…”[5] Biodiversity losses may range from individuals to populations to complete ecosystem collapse.[6]

The USGS estimates that agricultural irrigation accounts for about two-thirds of all groundwater withdrawals.[7] Broadly estimated, about one third or more of all groundwater withdrawals can be attributed to animal agriculture.[8]

Rohde, M. M., et al., (2024). Groundwater-dependent ecosystem map exposes global dryland protection needs. Nature, 632(8023), 101-107. Abstract [“Groundwater is the most ubiquitous source of liquid freshwater globally, yet its role in supporting diverse ecosystems is rarely acknowledged.”]

Devitt, T. J., et al., (2019). Species delimitation in endangered groundwater salamanders: Implications for aquifer management and biodiversity conservation. PNAS, 116(7), 2624-2633. [“The groundwater-obligate organisms (stygobionts) underpinning these ecosystem services are among the least-known components of global biodiversity, as well as some of the most vulnerable to extinction. They are particularly vulnerable because most have small distributions and are adapted to a narrow set of environmental conditions.”]

The Nature Conservancy (March 13, 2022) Groundwater: Our Most Valuable Hidden Resource. https://www.nature.org/en-us/what-we-do/our-insights/perspectives/groundwater-most-valuable-resource/

Blevins, E. & Aldous, A. (2011). Biodiversity value of groundwater-dependent ecosystems. The Nature Conservancy, WSP, 18-24. p. 22 [“Indeed, 26% of invertebrates, 23% of vertebrates, and 10% of vascular plants with federal listing were deemed groundwater-dependent in some way, with 17% overall.”]

Rohde, M. M., et al., (2024). Groundwater-dependent ecosystem map exposes global dryland protection needs. Nature (London), 632(8023), 101–107, p. 104.

Rohde, M. M., et al., (2024). Establishing ecological thresholds and targets for groundwater management. nature water, 2(4), 312-323.,p. 312. [“Groundwater-related adverse impacts range in severity from water stress (individual scale) to habitat loss (population scale) to, in the worst-case scenario, ecosystem collapse (system scale). Whereas some impacts may be reversible, others may result in the permanent loss of species and/or habitats.”]

Dieter, C.A., et al., (2018) Estimated Use of Water in the United States in 2015, U.S. Geological Survey, Table 4A, p. 14. [57.2 Bgal/day of groundwater (Table 4A) / 118 Bgal/day of all irrigation water withdrawals (Table 2A) = 48.47%.] [Total groundwater withdrawals for irrigation = 52.7 Bgal per day / 82.3 Bgal per day of all groundwater withdrawals == 69.5%]

See, Groundwater & Aquifer Depletion [question: What portion of all groundwater withdrawals can be attributed to animal ag?]

There are more than 92,000 dams in the U.S.[1] The U.S. has some of the highest concentrations of dams in the world.[2] Although irrigation is not the primary purpose of most U.S. dams, they are a significant source of irrigation water, especially in the Western states.[3,4] The Hoover dam alone is reported to irrigate a million acres in central Arizona.[5]

Dams fragment and degrade habitats in several ways:[6-10]

Dams reduce the size and connectivity of natural water habitats.

Dams prevent fish migration, limiting their ability to access spawning habitat, seek food, and escape predation.

Dams slow water movement which harms fish and other organisms that rely on steady flows.

Slow-moving or still reservoirs retain more heat, resulting in abnormal temperatures that affect species and lead to algal blooms.

Reservoirs are prone to lower oxygen levels leading to eutrophication.

Dams alter habitat by trapping sediment. Animals can also become caught behind accumulating logs and gravel.

Changing waterway conditions can favor invasive species that further transform conditions for native species.

National Inventory of Dams – U.S. Army Corps of Engineers [92,428 Total Dams]

https://nid.sec.usace.army.mil/#/Zhang, A. T. & Gu, V. X. (2023). Global Dam Tracker: A database of more than 35,000 dams with location, catchment, and attribute information. Scientific Data, 10(1), 111. [“The United States and Canada have some of the highest concentration of dams in the world.”]

Water Reliability in the West – 2021 SECURE Water Act Report. (2021) Prepared for the United States Congress. Bureau of Reclamation, Water Resources and Planning Office, p. 1. [States that the dams “provide one out of five farmers in the Western United States (West) with irrigation water for 10 million acres of farmland that produce 60 percent of the Nation’s vegetables and 25 percent of its fruits and nuts.” In 2023, 50.4M acres were irrigated, so this = ~20% of total irrigated acres.]

Billington, D. P., et al. (2005) The History of Large Federal Dams: Planning, Design, and Construction, U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Bureau of Reclamation, Denver, CO, p. 23 [“By the mid-1880s, most of the small streams in the West had been diverted for irrigation and other uses. It was becoming clear that larger dams on the major rivers would be needed to expand water supplies.”]

Di Baldassarre, G., et al., (2021). The legacy of large dams in the United States. Ambio, 50(10), 1798–1808, p. 1804. [“High demands from the agricultural section have made the Southwest heavily reliant on water infrastructure. As dam development has plateaued, wells are getting deeper and groundwater levels are declining too.”]

Tickner, D., et al., (2020). Bending the Curve of Global Freshwater Biodiversity Loss: An Emergency Recovery Plan. BioScience, 70(4), 330–342, p. 336. [“Dams and weirs fragment longitudinal (upstream to downstream) connectivity and, through flow alterations, also affect lateral (river to floodplain), vertical (surface to groundwater), and temporal (season to season) connectivity. Engineered levees and other flood management structures separate rivers from their floodplains.”]

NOAA Fisheries -How Dams Affect Water and Habitat on the West Coast.

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/west-coast/endangered-species-conservation/how-dams-affect-water-and-habitat-west-coastBarbarossa, V., et al., (2020). Impacts of current and future large dams on the geographic range connectivity of freshwater fish worldwide. PNAS, 117(7), 3648-3655, p. 3648. [Dams “affect freshwater ecosystems by inundation, hydrologic alteration, and fragmentation, for example. Fragmentation of the freshwater environment has major implications for freshwater fish as dams obstruct migration routes, essential for spawning or feeding, and limit dispersal.”]

Deinet, S., et al., (2024) The Living Planet Index (LPI) for migratory freshwater fish 2024 update – Technical Report. World Fish Migration Foundation, The Netherlands, p. 6. [“Dams and other river infrastructures change flow regimes, which affects the connectivity between habitats, and the timing and magnitude of lifecycle cues, and availability of habitat.”]

Pringle, C. M. (2000). Threats to U.S. Public Lands from Cumulative Hydrologic Alterations Outside of Their Boundaries. Ecological Applications, 10(4), 971–989, p. 972. [“Cumulative effects of dams, water impoundment, diversion, regulated flows, stream channelization, wetlands drainage, and groundwater extraction are often synergistic and they are increasingly altering the biological integrity of public lands; from disruption of the movement of migratory fishes and other wildlife which use riparian corridors to alteration of riparian vegetation, and the creation of conditions that allow the proliferation of undesirable exotic species in both aquatic and riparian habitats.”]

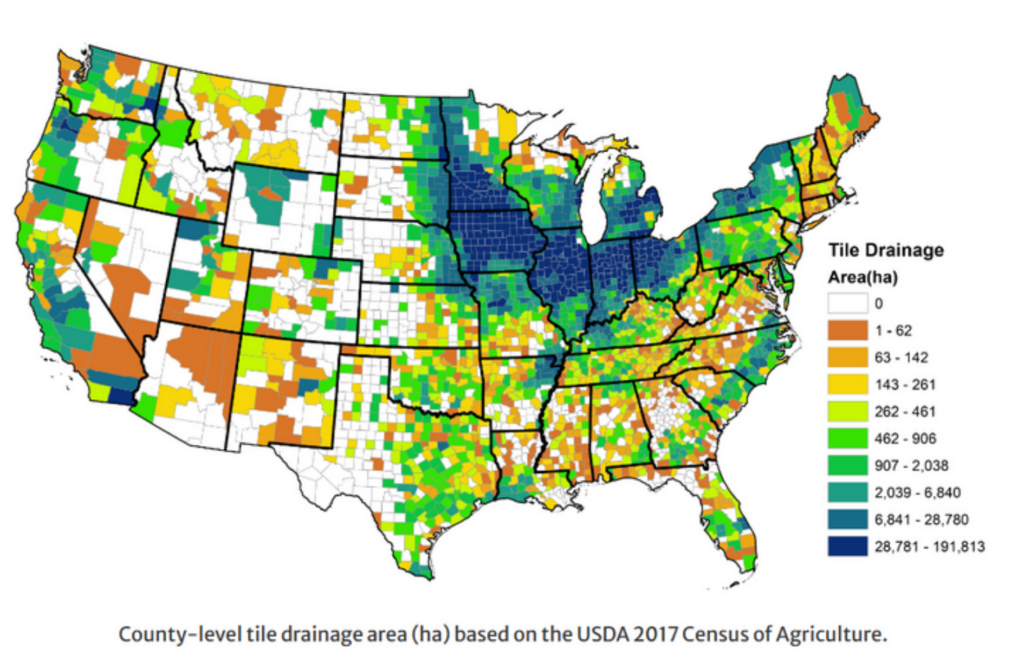

Because so much of the midwestern agricultural region was a wet-prairie ecosystem with poor drainage, “Bringing much of this land into production under modern agricultural systems has been associated with extensive modifications to natural drainage networks. Extensive networks of surface ditches and subsurface drains (“tiles”) have been constructed to remove excess water from the field soil surface or soil profile.”[1]

The result is to lower water tables in adjacent natural areas with negative impacts on plant communities and wildlife that rely on aquatic ecosystems. “The most significant aquatic ecosystem impact of drainage historically has been the direct loss and alteration of wetland and riparian habitats.”[2]

These wetlands are “among the most productive ecosystems in the world, comparable to forests and coral reefs.”[3,4] About half of all plant and animal species in the U.S. listed as threatened or endangered depend on wetlands for survival.[5]

Tile drainage area in the U.S. is heavily concentrated in the corn belt, where the vast majority of corn and soybean production occurs.[6] These management practices have led to the drainage of much of the historic wetland habitat. Along with removing excess water, tile drainage expedites transport of nutrients into downstream waters contributing to nutrient pollution and its enormous damage to freshwater biodiversity.[7-9]

Blann, K.L., et al., (2009), Effects of Agricultural Drainage on Aquatic Ecosystems: A Review. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 39: 11, 909, p. 910. [“By 1987, the most recent year for which survey data were collected, more than 17% of U.S. cropland (up to 30% in the Upper Midwest) had been altered by artificial surface or subsurface drainage.”]

Blann, K. L., et al., (2009), p. 919. [“Several recent assessments of aquatic biodiversity in agricultural landscapes have suggested that the combination of land use change, habitat and population fragmentation, and past disturbance has created an extinction debt that is likely to drive continuing biodiversity declines even if current threats are ameliorated.”]

U.S. EPA (2024) Why are Wetlands Important? [See series of EPA Factsheets for further wetland info] Also, U.S. EPA (2024) National Wetland Condition Assessment: The third collaborative survey of wetlands in the United States. EPA 843-R-24-001. https://wetlandassessment.epa.gov/webreport (Online only)

U.S. EPA (2004) Wetlands Overview. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2021-01/documents/wetlands_overview.pdf

Lang, M.W., et al., (2024). Status and Trends of Wetlands in the Conterminous United States 2009 to 2019. U.S. Department of the Interior; Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C., p. 6. [“Wetlands enhance water quality, control erosion, maintain stream flows, sequester carbon, and provide a home to about half of all threatened and endangered species.”]

Map from: Valayamkunnath, P., et al., (2020). Mapping of 30-meter resolution tile-drained croplands using a geospatial modeling approach. Scientific Data, 7(1), 257–257.

Mitchell, M. E., et al., (2023). A review of ecosystem services from edge-of-field practices in tile-drained agricultural systems in the United States Corn Belt Region. Journal of Environmental Management, 348(C), 119220–119220, p. 1. [Tile drainage systems “expedite subsurface nitrate transport from agricultural systems, resulting in losses of nitrogen from the fields where it is needed and contributing to nitrate pollution in downstream surface waters. Additionally, the capacity for tile drain systems to remove water from fields has led to the drainage of much of the historic wetland habitat important for amphibians and waterbirds in the US Corn Belt.”]

See, Fertilizer & Manure Harm to Biodiversity

Benton, T.G., et al., (2021) Food system impacts on biodiversity loss: Three levers for food system transformation, Chatham House, ISBN 978-1-78413-433-4, p. 15. [“Our current food system is structured to drive demand, leading to biodiversity loss through (1) the continued conversion of natural or semi-natural ecosystems to managed ones, and (2) the use of unsustainable agricultural practices at farm level, landscape level and global level.”]