1. Globally, grazing is understood to be the number one driver of land degradation.

2. U.S. grazing lands are undergoing pervasive and accelerating degradation; a broad and conservative estimate is that one-third or more of U.S. grazing lands are degraded.

3. Because grazing makes up the single largest use of land in the U.S., this has an enormous negative impact on the 3 central components of land degradation – soil, water, and biodiversity.

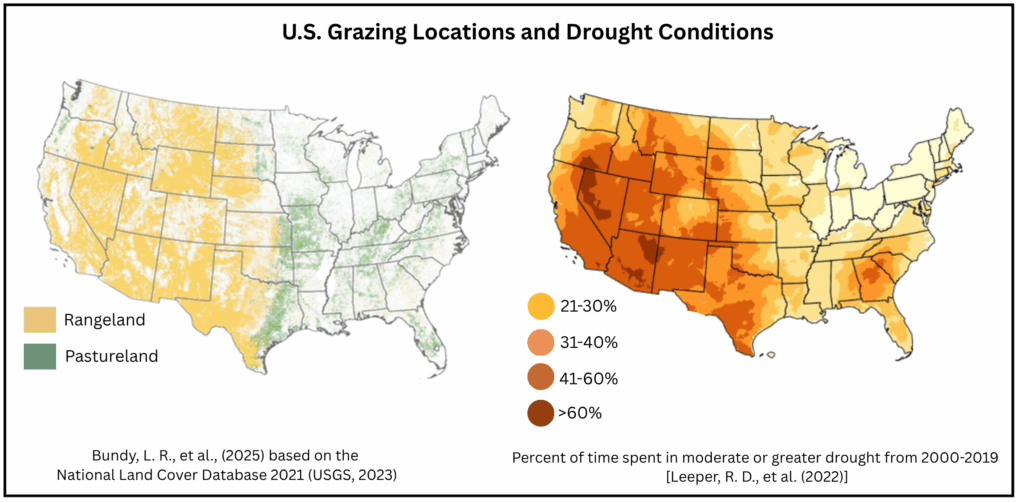

4. Most U.S. grazing occurs on western drylands. These are arid or semi-arid regions which are inherently vulnerable lands.

5. Western dryland conditions are deteriorating at an accelerating rate due to grazing pressures along with climate change and drought.

6. These facts are obscured due to cultural, political, and economic factors, targeted misinformation, and federal agency failures to clearly state the national status and trends of grazing land conditions.

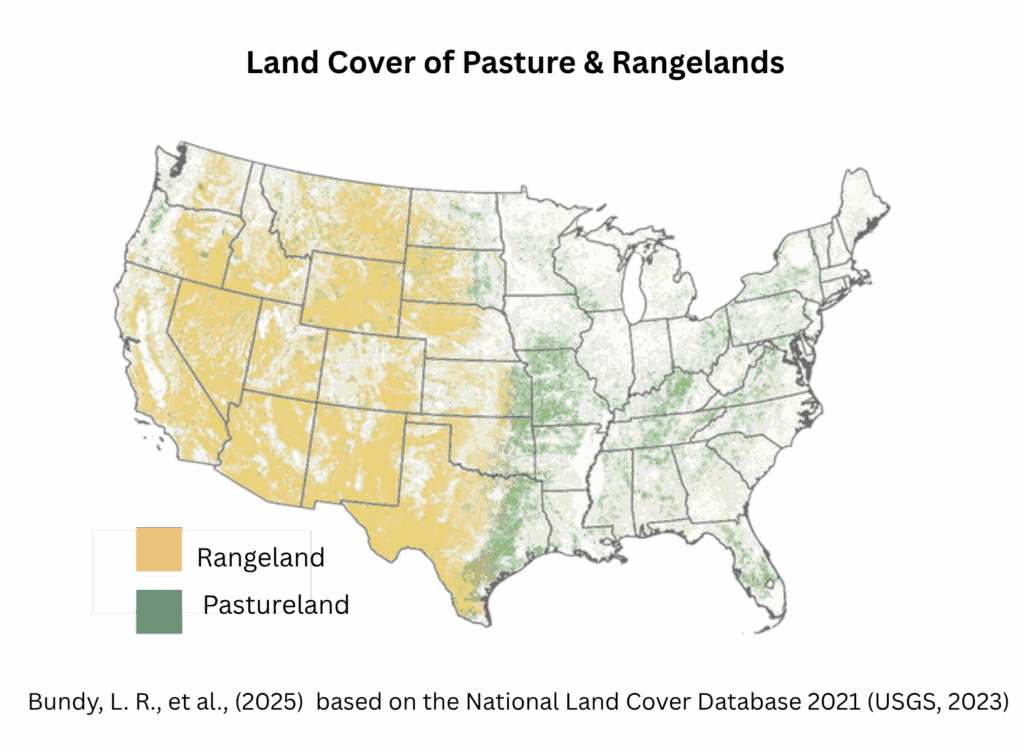

Grazing lands are generally divided into rangeland and pastureland.

Rangelands – are made up of mostly native plants that are uncultivated.[1,2]

Pasturelands – are made up of mostly introduced forage plants that are cultivated.[3,4]

Pellant, M., et al., (2020) Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health, Version 5. Tech Ref 1734-6, Bureau of Land Management, Table 1, p. 5. [Rangelands are “lands on which the indigenous vegetation (climax or natural potential) is predominantly grasses, grass-like plants, forbs, or shrubs and is managed as a natural ecosystem. If plants are introduced, they are managed similarly.”]

USDA NALT Glossary [Rangelands defined as “Land on which the historic climax plant community is predominantly grasses, grasslike plants, forbs, or shrubs. Includes lands revegetated naturally or artificially when routine management of that vegetation is accomplished mainly through manipulation of grazing. Rangelands include natural grasslands, savannas, shrublands, most deserts, tundra, alpine communities, coastal marshes.”]

USDA NRCS Pasture Resources. [“Pasture is a land use type having vegetation cover comprised primarily of introduced or enhanced native forage species that is used for livestock grazing. Pasture receives periodic renovation and cultural treatments such as tillage, fertilization, mowing, weed control, and may be irrigated.”]

Bundy, L. R., et al., (2025). United States pasture and rangeland conditions: 1995–2022. Agronomy Journal, 117(1), e21736, p. 1. [“Pastures are defined as land used for herbaceous forage crops that are highly managed and cultivated, while rangelands are an area of shrub and/or natural grass ecosystems primarily used for extensive livestock production.”]

Broadly estimated, about 670 million acres are used for grazing as their “primary use.” This is about 35% of the contiguous U.S.[1]

Broadly estimated, of the total acres of grazing land:

Rangelands (~540 million acres) About 400 million acres are privately-owned rangelands.[2]

About 140 million acres are federally owned rangelands.[3]

Pastureland (~130 million acres) About 120 million acres are privately-owned pastureland.[4]

About 10 million acres are privately owned croplands used for pasture.[5]

Rangelands make up the bulk of grazing lands, ~540 million acres. They are mostly in Western states.[6]

Winters-Michaud, C., et al., (2024) Major Uses of Land in the United States, 2017. USDA ERS Bulletin No. 275, Table 1, p. 5. [Total land area contiguous U.S. = 1,891.1M acres; Grazing land = 671M acres. We do not include 132M acres of “forest-use land” categorized by Winters-Michaud as grazing land since it is not the “primary use.” Of these acres, broadly estimated, ~70M acres are federally owned (see, USDA Forest Service (2021) Grazing Statistical Summary Fiscal Year 2021, p. 5) and ~60M acres are privately owned forest lands (estimated from Winters-Michaud, Figure 11, p. 36)

USDA (2020) Summary Report: 2017 National Resources Inventory, NRCS and Center for Survey Statistics and Methodology, Iowa State University, p. 2-1. [Non-federal rangeland = 403.9M acres. Note: chart includes Hawaii and Caribbean islands at ~1M acres]

Note: Between the BLM and the Forest Service, about 213M acres were actively grazed in 2017. See, Grazing on Federal Lands [question “How many federal acres are actively grazed?”] We are not aware, however, of the BLM or US Forest Service breaking down their active grazing acreage into rangelands and grazed forests. Therefore, we use the “total grazed forest-use” figure from Winters Michaud (Table 9, p. 32) and subtract the estimate of “private forest land grazed” (estimated from Winters-Michaud, Figure 11, p. 36) to arrive at ~70M acres for federal grazed forest (which coincides with Forest Service use of 74M acres). That puts grazed federal rangelands at ~140 million acres (213M – 70M = ~140M) which seems reasonable.

USDA (2020) Summary Report: 2017 National Resources Inventory, p. 2-1. [Non-federal pastureland = 121.6M acres. Note: chart includes Hawaii and Caribbean islands at ~0.5M acres]

Winters-Michaud, C., et al., (2024) Major Uses of Land in the United States, 2017. USDA ERS Bulletin No. 275, Table 1, p. 5. [Cropland used for pasture = 13M acres]

Grazing map: Bundy, L. R., et al., (2025). United States pasture and rangeland conditions: 1995–2022. Agronomy Journal, 117(1), e21736, Figure 1, p. 3.

Grazing at moderate to heavy levels or on vulnerable lands[1,2] can degrade land in a variety of ways:[3-9]

Decreasing the diversity of plant and animal species, especially native species.

Decreasing biomass above ground and in soils.

Reducing food supplies for birds and pollinators and removing cover from predators for small mammals.

Trampling and compacting soils and biotic soil crusts (communities of organisms that form a crust-like layer in arid regions) that protect against wind erosion and dust emissions.

Degrading streams and streambanks due to excess congregation in wet areas, and reducing aquatic vegetation, crucial for fish and aquatic organism survival.

Decreasing water quality and increasing pollution from excess nutrients and from sedimentation from trampled banks.

Dispersing invasive species or creating favorable conditions for their establishment.

Thwarting animal movement and migration patterns with livestock fencing.

Note: All reports on the impacts of grazing distinguish between levels of grazing intensity and the inherent vulnerability of the regions assessed. In general, it can be stated that light grazing is not viewed as a detriment to the land except in highly vulnerable areas. Moderate to heavy grazing is generally viewed as problematic, especially in arid regions. Because of the wide range of grazing methodologies, levels of intensity, and biomes, generalizing about grazing is especially challenging. (See next footnote and next few questions.)

Hovick, T. J., et al., (2023) Rangeland Biodiversity, in Rangeland Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, McNew, L. B., et al. (Eds.), p. 217. [“The influence of livestock grazing on wildlife is largely dependent upon the spatial and temporal distribution of the grazer and may also be influenced by livestock type, timing and frequency of grazing, grazing duration, livestock distribution across the landscape, seasonality, stocking rate, and the evolutionary history of grazing at a given site.”]

Beschta, R. L., et al., (2013). Adapting to Climate Change on Western Public Lands: Addressing the Ecological Effects of Domestic, Wild, and Feral Ungulates. Environmental Management, 51(2), 474–491, p. 476. [“…extensive reviews of published research generally indicate that livestock have had numerous and widespread negative effects to western ecosystems. Simplified plant communities combine with loss of vegetation mosaics across landscapes to affect pollinators, birds, small mammals, amphibians, wild ungulates, and other native wildlife.”]

Kauffman, J. B., et al., (2022). Livestock Use on Public Lands in the Western USA Exacerbates Climate Change: Implications for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation. Environmental Management, 69(6), 1137–1152, p. 1139. [“Regardless of season of use or grazing intensity, domestic livestock generally influence ecosystems in four direct ways: (1) by removing vegetation through grazing; (2) by trampling soils, biotic soil crusts, streambanks and vegetation; (3) by redistributing nutrients via defecation and urination; and (4) by dispersing or creating favorable conditions for the establishment and dominance of exotic organisms, including noxious plant species and pathogens.”]

Zhou, G., et al., (2017). Grazing intensity significantly affects belowground carbon and nitrogen cycling in grassland ecosystems: A meta‐analysis. Global change biology, 23(3), 1167-1179, p. 1174. [Meta-analysis found, “Specifically, grazing decreased aboveground biomass… indicated a decrease in soil microbial biomass in grazed areas.”]

Hubbard, R. K., et al., (2004). Water quality and the grazing animal. Journal of Animal Science, 82 E-Suppl, E255–E263, p. E255. [“Grazing animals and pasture production can negatively affect water quality through erosion and sediment transport into surface waters, through nutrients from urine and feces dropped by the animals and fertility practices associated with production of high-quality pasture, and through pathogens from the wastes.”]

Belsky, A. J., et al., (1999). Survey of livestock influences on stream and riparian ecosystems in the western United States. Journal of Soil and water Conservation, 54(1), 419-431, p. 3 & 5. [“Cattle tend to avoid hot, dry environments and congregate in wet areas for water and forage, which is more succulent and abundant than in uplands… Most authors tended to agree that livestock damage stream and riparian ecosystems.”]

Filazzola, A., et al., (2020). The effects of livestock grazing on biodiversity are multi-trophic: a meta-analysis. Ecology Letters, 23, p. 1304. [“Across all animals, we found excluding livestock increased animal abundance and diversity that was likely driven by strong effects on trophic levels directly dependent on plants (i.e. herbivores and pollinators).” “We found evidence that livestock exclusion increased the abundance of plants and over time, plant diversity.”]

Jakes, A. F., et al., (2018). A fence runs through it: A call for greater attention to the influence of fences on wildlife and ecosystems. Biological Conservation, 227, 310-318.

Inherent risk – All grazing lands are vulnerable to degradation. Globally, it is understood that grazing is the primary driver of land degradation.[1-3]

Arid regions – Most U.S. grazing lands are rangelands in arid or semi-arid regions.[4,5] These are the lands most vulnerable to degradation and even desertification.[6,7]

Worsening conditions – Warming temperatures due to climate change, increasing drought, and more wildfires are adding to the risks.[8-10] Federal agencies and agency scientists acknowledge the growing risks and worsening conditions.[11,12]

Ruben Coppus (2023) The global distribution of human-induced land degradation and areas at risk. SOLAW21 Technical background report. FAO, p. iv. [“Grazing is the most common occurring driver of human-induced degradation, followed by accessibility and agricultural expansion.”]

For detailed on-line dataset from Coppus above, see, FAO (2025) Human-induced degraded land by country and land cover/land use type (Guilia Conchedda, producer). [Agricultural degradation (1,038,342,273 hectares) is ~63% of total land degradation (1,651,468,927 hectares). Of total degradation, grazing is responsible for ~34% and cropland is responsible for ~29%.]

IPBES (2018) The IPBES assessment report on land degradation and restoration. Montanarella, L., et al., (eds.) Secretariat of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, p. v. [“While the unsustainable management of croplands and grazing lands is currently the most extensive direct driver of land degradation, climate change can exacerbate the impacts of land degradation and can limit options for addressing land degradation.”]

Grazing map: Bundy, L. R., et al., (2025). United States pasture and rangeland conditions: 1995–2022. Agronomy Journal, 117(1), e21736, Figure 1, p. 3. [“Land cover of pastures and rangelands at 30-m spatial resolution for the conterminous United States based on the National Land Cover Database 2021 (USGS, 2023).”]

Drought map: Leeper, R.D., et al., (2022) Characterizing U.S. drought over the past 20 years (using the U.S. drought monitor). Int. J. Climatol., 42:6616–6630, figure 3, p. 6620. [map shows the percent of time spent in D1 (moderate drought) or greater drought status from 2000 through 2019]

IPBES (2018) The IPBES assessment report on land degradation and restoration, p. 141. [“Over half of grazing lands occur in dryland environments that are highly susceptible to land degradation.”]

Huang, J., et al., (2020). Global desertification vulnerability to climate change and human activities. Land Degradation & Development, 31(11), 1380-1391, Figure 3, p. 4. [“The high level of desertification risk is mainly in the western part of the United States, the Sahel, central Asia, and northern China, where vegetation is sparse (Figure 2c) and the climate is dry (Figure 2b).” at p. 5]

Steinfeld, H., et al., (2019). Overview paper: Livestock, Climate and Natural Resource Use, Kansas State Univ., p. 6. [“Predicted changes in climate and weather are likely to result in more variable pasture productivity and quality, increased livestock heat stress, greater pest and weed effects, more frequent and longer droughts, more intense rainfall events, and greater risks of soil erosion.”]

Bundy, L. R., et al., (2025), p. 2 & 14. [“Therefore, the onset of drought and extreme rainfall events, in addition to warmer summers, land fragmentation, and invasive non-native species, will continue to have negative impacts on grazing systems across the United States.” “…large fires on western US grazing lands have also increased more than fivefold during the 1984–2017 epoch…]

Williams, A. P., et al., (2022). Rapid intensification of the emerging southwestern North American megadrought in 2020–2021. Nature Climate Change, 12(3), 232-234. [For the Southwest, “We find that 2000–2021 ranks as the driest 22-yr period since at least 800 CE…Both 2002 and 2021 were probably drier than any other year in nearly three centuries…”]

Reeves, M., et. al., (2023) Rangeland Resources. In: USDA Forest Service (2023). Future of America’s Forest and Rangelands: Forest Service 2020 Resources Planning Act Assessment. Gen. Tech. Rep. WO-102, 8-1–8-33. Chapter 8. [“Prolonged droughts in the Southwestern United States and California are creating novel conditions that have not been experienced since well before Euro-American settlement. These conditions are expected to occur with greater frequency in the future, creating ecological, social, and economic challenges.”]

Charnley, S., et al., (2025). Managing for Flexibility on US Forest Service Grazing Allotments. Rangeland Ecology & Management, 101, 64-79, Abstract. [“Many ranchers in the western U.S. operate in a rangeland environment characterized by seasonal and annual fluctuations in water and forage, recurring drought, spreading invasive plants, increased wildfire, warming temperatures, shifting grazing seasons, and predators. Climate change is predicted to exacerbate these characteristics.”]

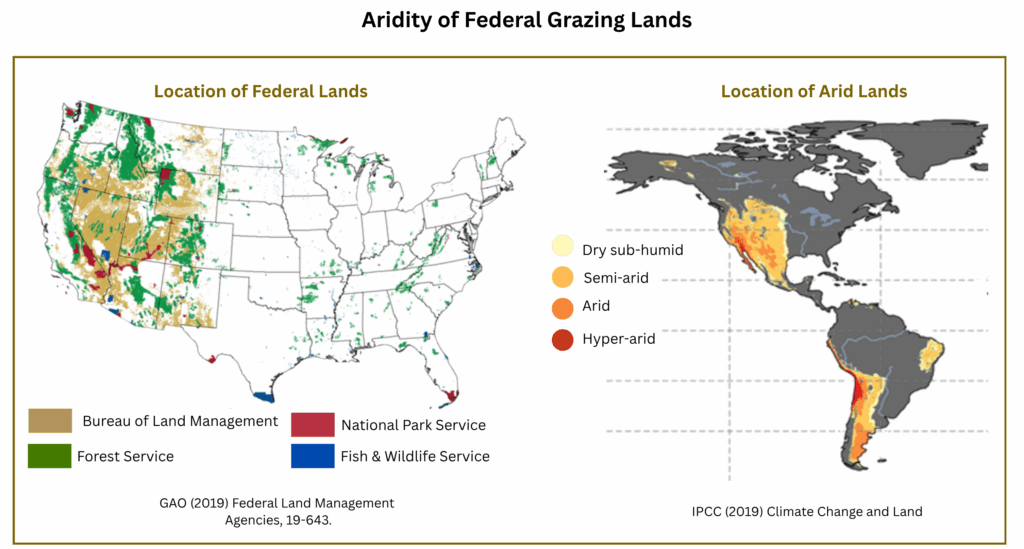

Federal grazing lands are almost exclusively in arid regions, particularly vulnerable to degradation.[1,2]

Because the land is public, it is subject to the “the tragedy of the commons.”[3] Degradation due to grazing on public lands exemplifies the concept and is how the term originated.[4] If conditions become degraded, ranchers can simply relocate.

Fees for grazing on public lands equal ~6% of average fees for private lands and are nominally the same as 50 years ago, encouraging grazing usage.[5]

The extent of unauthorized grazing is unknown.[6] According to the GAO, “Unauthorized grazing may create various effects, such as severely degrading rangelands under certain conditions.”[7] Unauthorized grazing may be unintentional or intentional.[8] The minor financial penalties for unauthorized grazing are not sufficient to deter the practice.[9]

Each officer available to enforce grazing regulations oversees between a half million and more than one million acres.[10] Officers are fearful of retribution.[11] The ownership, use, regulation, and protection of federal lands are highly controversial subjects.[12]

Map 1- GAO (2019) Federal Land Management Agencies: Additional Actions Needed to Address Facility Security Assessment Requirements, GAO-19-643, p. 7.

Map 2 – IPCC (2019) Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems (P.R. Shukla, et al., eds.), Technical Summary, Figure TS.6, p. 51.

Note: The concept known as “the tragedy of the commons” refers to a publicly owned resource being overused or exploited due to individual or institutional self-interests overriding the public good.

Andrew Barkley & Paul W. Barkley (2013) Principles of Agricultural Economics. Routledge, London. ISBN 978-0-415-54-69-8, p. 331. [“The tragedy of the commons is most often described in terms of grazing and overgrazing publicly owned ranch land… The reason is that there are no costs (or very low costs) associated with using the land, so ranchers continue to use the land past the point of sustainability, to exploitation, or overuse. This outcome is typical of public land use for grazing animals, hunting, fishing, and camping.”]

See, Grazing on Federal Lands. [The fees received by federal agencies are not large enough to cover the costs to administer the programs. See: Congressional Research Service (2019) Grazing Fees: Overview and Issues, RS21232, p. 2. [“BLM and FS typically spend more managing their grazing programs than they collect in grazing fees. For example, $79.0 million was appropriated to BLM for rangeland management in FY2017. Of that amount, $32.4 million was used for administration of livestock grazing, according to the agency.”]

GAO (2016) Unauthorized Grazing: Actions Needed to Improve Tracking and Deterrence Efforts , p. 12 and p. 15. [“The frequency and extent of unauthorized grazing on Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and U.S. Forest Service lands are largely unknown…” “…compliance monitoring of grazing is critical because just a few weeks of unauthorized grazing can set back years of progress in restoring riparian areas.”]

GAO (2016) Unauthorized Grazing: Actions Needed to Improve Tracking and Deterrence Efforts, p. 12.

CRS (2019) Grazing Fees: Overview and Issues, p. 9-10. [“In many cases the unauthorized grazing is unintentional, but in other cases livestock owners have intentionally grazed cattle on federal land without getting a permit or paying the required fee. The livestock owners have claimed that they do not need to have permits or pay grazing fees for various reasons, such as that the land is owned by the public; that the land belongs to a tribe under a treaty; or that other rights, such as state water rights, extend to the accompanying forage.”]

GAO (2016) Unauthorized Grazing: Actions Needed to Improve Tracking and Deterrence Efforts. [“For example, most of the Forest Service staff GAO interviewed said that unauthorized grazing penalties are too low to act as an effective deterrent.”]

GAO (2019) Federal Land Management Agencies: Additional Actions Needed to Address Facility Security Assessment Requirements, Figure 7, p. 29. [The BLM has one enforcement officer per 1.3 million acres while the Forest Service has one per 460,000.]

GAO (2019) Federal Land Management Agencies: Additional Actions Needed to Address Facility Security Assessment Requirements, p. 14. [“… incidents ranged from threats conveyed by telephone to attempted murder against federal land management agency employees.”]

Congressional Research Service (2020) Federal Land Ownership: Overview and Data, Summary, Report R42346, p. 4. [“Ownership and use of federal lands have stirred controversy for decades. Conflicting public values concerning federal lands raise many questions and issues, including the extent to which the federal government should own land…”]

According to credible though incomplete federal data, 40-50% of assessed federal grazing lands show clear evidence of degradation:[1,2]

Assessed by the BLM – The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) is required to establish standards and assess grazing land health.[3] For the year 2024, the BLM reported that 42% of all BLM rangeland acreage was compromised and could not be rated as “healthy.”[4] (About a quarter of all grazing land is federally owned and administered.)[5]

Reported by PEER – The non-profit PEER (Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility) has repeatedly reported on land status gathered from internal BLM assessments received through FOIA requests. The 2024 PEER report states that for the period from 1997-2023, the BLM determined that of the total acres assessed, 50% (57 million acres) failed to meet rangeland health standards. Of the failed acres, two-thirds were due to livestock overgrazing.[6] Peer concludes that, “Overall, the comparison of 2019 and 2023 rangeland health data underscores the dramatic impact of overgrazing by livestock on our public lands.”[7,8]

U.S. Forest Service – The USFS does not conduct regular evaluations of rangeland health attributes.[9]

Note: We focus on federal agency reports because a) they are detailed and comprehensive, b) there are very few refereed journal reports that assess conditions nationally (or researchers that have the resources to do so), and c) the literature is filled with misinformation put out by non-objective parties.

The BLM assesses rangelands “healthy” when all three rangeland health attributes (soil and site stability, hydrologic function, and biotic integrity) had a “none-to-slight” or “slight-to-moderate” “degree of departure from reference conditions.” These determinations are based on: Pellant, M., et al., (2020) Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health, Version 5. Tech Ref 1734-6, Bureau of Land Management, Table 1 & Table 2, p. 8. [To determine the share of “unhealthy” or “degraded” (our words) rangelands we use the inverse ratio (100% – 58% = 42% degraded. This is the share of rangelands that show moderate, moderate to extreme, or extreme to total departure from reference conditions.]

Code of Federal Regulations 43 CFR § 4180.

Bureau of Land Management (2025) Public Land Statistics 2024, Vol. 209, Table 2-1, p. 37. [For at least one of the three rangeland health attributes (soil and site stability, hydrologic function, and biotic integrity), 42% of acreage had between a moderate and total “departure from reference conditions.”]

See, Grazing on Federal Lands [question: “How many federal acres are actively grazed?”] Currently about 213 million federal acres are grazed of approximately 800 million total acres. About 65% (~140M acres) is managed by BLM, with ~75M acres managed by US Forest Service.

Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER) (2024) Evaluating Trends in Rangeland Health on Bureau of Land Management Lands, Table 1, p. 3 & 7. [Calculation: 37.9 million acres failed due to livestock overgrazing / 56.8 million failed acres = 66.7%. An additional significant share of failed acreage (6.5 million acres or ~11%) was due to a combination of “livestock and wild horses.” ( p. 7) PEER pieces together the information based on FOIA requests from multiple public records from state and field offices.]

PEER (2024) Evaluating Trends in Rangeland Health on Bureau of Land Management Lands. p. 18.

PEER (2022) BLM Land Health Status – BLM Identifies Millions of Acres of Failing Lands. This 2022 PEER report for the period 1997-2019 similarly identifies 50% of lands failing to meet standards, with 72% due to grazing. See Table 1, p. 8, “Not-Met Livestock.”

Reeves, M., et. al., (2023) Rangeland Resources. In: USDA Forest Service (2023). Future of America’s Forest and Rangelands: Forest Service 2020 Resources Planning Act Assessment. Gen. Tech. Rep. WO-102, 8-1–8-33. Chapter 8, p. 8-12. [“The USDA Forest Service has conducted the FIA All Conditions Inventory (ACI) sporadically on National Forest System lands in the Western United States since 2004. Unlike the NRI and AIM projects, the ACI protocols do not evaluate rangeland health attributes so no formal comparison can be made with non-Federal (NRI) or BLM (AIM/LMF) lands.”]

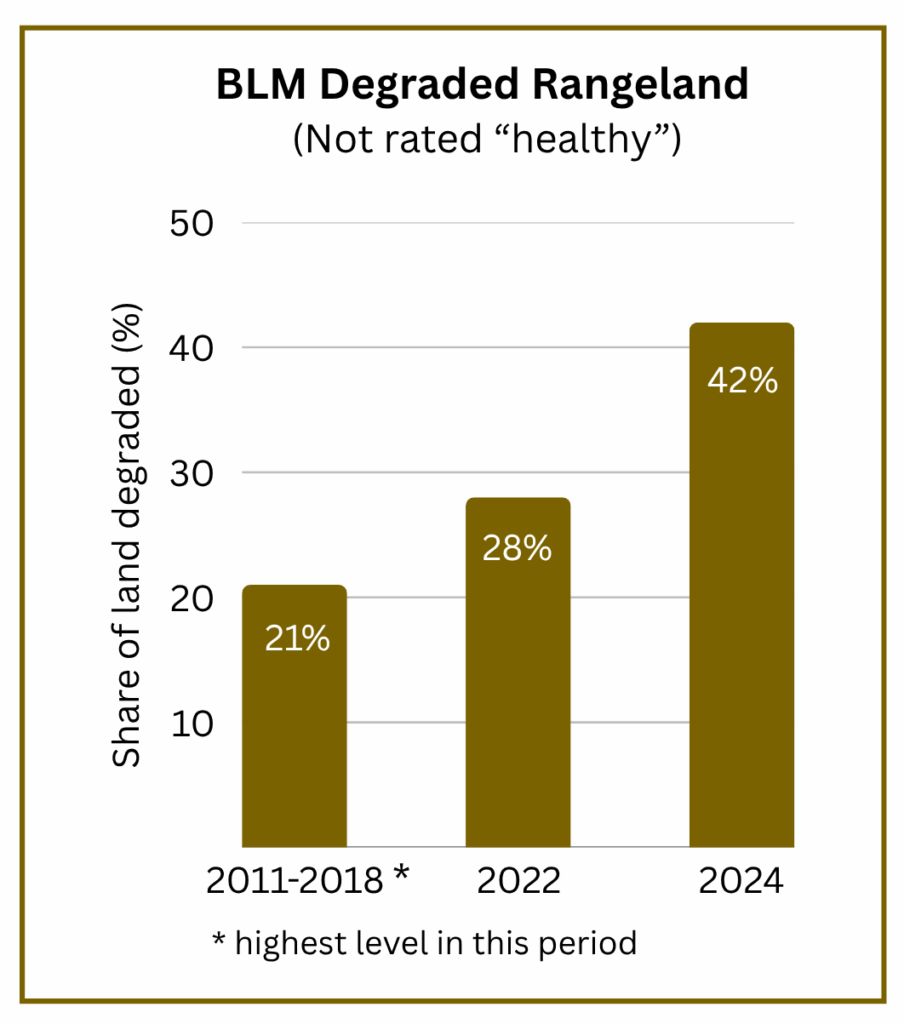

For BLM grazing lands, the share of degraded (not “healthy”) land has doubled in just a few years.

In the period from 2011-2018, the highest level of rangeland degradation was 21%.[1]

The BLM reported that 28% of rangeland acreage was degraded in 2022.[2]

The BLM reported that 42% of all rangeland acreage was degraded in 2024.[3]

The BLM does not use the term degradation. They report the findings in inverse proportions – that 58% of BLM managed rangelands (grazing lands) were “healthy.”

Reeves, M., et. al., (2023) Rangeland Resources. In: USDA Forest Service (2023). Future of America’s Forest and Rangelands: Forest Service 2020 Resources Planning Act Assessment. Gen. Tech. Rep. WO-102, 8-1–8-33. Chapter 8, p. 8-8. [“Between 79 and 86 percent of BLM rangelands from 2011 to 2018 exhibited less-than-moderate departure from reference conditions for the three rangeland health attributes. Conversely 14 to 21 percent of BLM rangelands exhibited moderate-to-extreme departure in one of the three rangeland health categories.”]

Bureau of Land Management (2023) Public Land Statistics 2022, Vol., Table 2-1, p. 36.

Bureau of Land Management (2025) Public Land Statistics 2024, Table 2-1, p. 37. [We use the term degraded because the BLM uses similar indicators to those used internationally to assess land degradation: “soil and site stability, hydrologic function, and biotic integrity.” What we refer to as “degraded” are those lands that the BLM determined have a “moderate” or greater “departure from reference conditions” in at least one of these 3 areas. See, footnote c, p. 38]

Taken together, the following 4 reports suggest that between a quarter and a half of U.S. private grazing lands are degraded.

1. National Resources Inventory Rangeland Resource Assessment – A study conducted by the USDA National Resource Conservation Service found that during 2011 to 2015: ~26% of privately-owned rangeland was compromised, i.e., “showed a rating of either moderate, moderate-to-extreme, or extreme-to-total departure from reference conditions for at least one of the three rangeland health attributes.”[1]

Biotic integrity (i.e., biodiversity) was “moderately compromised” or worse on ~23% of the assessed lands.[2]

2. USDA Pasture and Rangeland Conditions – A 2025 study reviewed the USDA’s weekly reports over a 28-year period. On average, during the warm season of each year, it found that about 45% of grazing lands were in good or excellent condition, and about 55% were in fair, poor, or very poor condition.[3,4]

3. National Range and Pasture Handbook – In 2022 the USDA issued a review of private grazing lands (2004-2018) outlining “rangeland resource concerns.”[5] According to a USDA recap of those results, the “dominant concerns” were:[6] Noxious and invasive plant species: 62% of the total area.

Productivity health and vigor: 44% (plant volume, quality, and soil cover.)

Forage quality and palatability: 37%.

Sheet and rill erosion (20%), gully erosion (17%) and wind erosion (11%).

4. NRI Pastureland Assessment – In a 2022 NRCS assessment, common “resource concerns” included (broadly estimated):[7] An abundance of invasive plants affecting ~50% of acres.

Soil compaction on ~25% of acres.

Soil organic matter depletion on ~15% of acres.

Soil erosion on ~10% of acres.

Spaeth, K. E., et al., (2024) Insights from the USDA Grazing Land National Resources Inventory and field studies. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, p. 38A. [This USDA report analyzes data from the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) (2018) National Resources Inventory Rangeland Resource Assessment.]

Spaeth, K. E., et al., (2024), Table 2, p. 39A. [“Biotic integrity: the capacity of the biotic community to support ecological processes within the natural range of variability expected for the site, to resist a loss in the capacity to support these processes, and to recover this capacity when losses do occur. The biotic community includes plants (vascular and nonvascular), animals, insects, and microorganisms occurring both above and below ground.” See National Range and Pasture Handbook, p.645-C.16.]

Bundy, L. R., et al., (2025). United States pasture and rangeland conditions: 1995–2022. Agronomy Journal, 117(1), e21736, p. 5. [“During the warm season over the 1995–2022 study period, on average, 45% of US grazing land acreage was in favorable condition where these lands provided adequate or an excess of feed (excellent or good condition), whereas the remaining 55% of acreage was in a less-than-ideal condition that required some extent of supplemental feeding to maintain livestock (fair, poor, or very poor.)”]

Bundy, L. R., et al., (2025), Figure 6, p. 2. [A visual analysis shows approximate values of excellent 10%, good 35%, fair 30%, poor 15%, and very poor 10%.]

USDA NRCS. (2022) National Range and Pasture Handbook. National Resources Conservation Service.

Spaeth, K. E., et al., (2024), p. 39A. [“Productivity, Health and Vigor = Plants do not produce the yields, quality, and soil cover to protect the resource.” See National Range and Pasture Handbook, p. 645-C.2]

USDA NRCS (2022) NRI Pastureland Assessment, Resource Concerns on Pastureland, Table 9. [These figures are a broad estimate of averages across 6 geographic regions.]

Two reports point to steadily declining conditions:

1. NRI Rangeland Resource Assessment – A study conducted by the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, found that during 2011 to 2015, ~26% of privately-owned rangeland was compromised, and “showed a rating of either moderate, moderate-to-extreme, or extreme-to-total departure from reference conditions for at least one of the three rangeland health attributes. This was a 7.5% increase over the period 2004-2010.”[1]

2. USDA Pasture and Rangeland Conditions – A 2025 study reviewed USDA weekly reports of nationwide pasture and rangeland conditions over a 28-year period. From 1995 to 2022, very poor conditions increased by 6%.[2] Comparing 1995 conditions (the best conditions in the 28 year period) to those of 2021 (one of the worst) points out the declining conditions.[3]

Spaeth, K. E., et al., (2024) Insights from the USDA Grazing Land National Resources Inventory and field studies. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, p. 38A. [During 2011 to 2015, 25.8% of nonfederal rangeland showed a rating of either moderate, moderate-to extreme, or extreme-to-total departure from reference conditions for at least one of the three rangeland health attributes. This was a 7.5% increase over 2004 to 2010 (table 2).” This USDA report analyzes data from the Natural Resources Conservation Service (2018) National Resources Inventory Rangeland Resource Assessment.]

Bundy, L. R., et al., (2025). United States pasture and rangeland conditions: 1995–2022. Agronomy Journal, 117(1), e21736. [Excellent conditions decreased by 2%, good decreased by 5%, poor conditions increased by 1%, and very poor conditions increased by 6%]

Bundy, L. R., et al., (2025), p. 8. [In 1995 excellent/good = 57%. Poor/ very poor = 13%. In 2021 excellent/good = 28% and poor/very poor = 42%]

Based on the reports reviewed above, a broad and conservative estimate is that one-third or more of U.S. grazing lands are degraded.[1,2]

We use the words degraded and degradation throughout these pages, despite U.S. federal agencies steadfastly avoiding the term. As we have noted on other posts, the USDA often uses “resource concerns.” For rangelands and pasturelands the USDA or BLM often uses terms depicting the share that are “healthy,” or the share of rangelands where all three rangeland health attributes (soil and site stability, hydrologic function, and biotic integrity) had a none-to-slight or slight-to-moderate departure from reference conditions. We do not use the term “land degradation” as it is defined internationally – i.e., that land is considered “degraded” only if the drivers are anthropogenic. U.S. federal reports rarely make a distinction between natural and anthropogenic drivers. In a time of climate change, drought, and invasive species, this distinction becomes even more difficult to draw.]

Broad calculation: If 25-50% of private grazing lands are degraded (75% of total grazed lands) and 40-50% of federal lands (25% of grazing land) then (.375 * .75) = .28 + (.45 * .25) = .11 == 39%.

In the U.S., the term “degradation” is rarely used by U.S. federal agencies, while a variety of obscure terms and phrases are more common.[1-3]

Land degradation is inherently difficult to define and measure.[4]

There are few national assessments.[5,6]

The USDA, in its role promoting agriculture, steadfastly avoids broad evaluations that might clarify or confirm the high levels of degradation.

See, Land Degradation & Animal Ag for a more complete review [question: “Why is the status of U.S. land degradation obscured?”]

For croplands, the common term used by the USDA is “resource concerns.” Also used are “resource monitoring” or “resource assessment.” See, for example: Rosenberg, A. B., et. al., (2022). USDA Conservation Technical Assistance and Within-Field Resource Concerns, EIB-234, USDA ERS.

For grazing lands, the common term is generally “departure from reference conditions” or “departure from the reference state.” See, Pellant, M., et al., (2020) Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health, Version 5. Tech Ref 1734-6, Bureau of Land Management, Table 1, p. 8 & 15.

Gibbs, H. K., & Salmon, J. M. (2015). Mapping the world’s degraded lands. Applied geography, 57, 12-21, p. 13. [“Simply to define “degradation” is challenging and likely contributes to the apparent variance in estimates.”]

U.S. EPA (updated July 25, 2024) Biodiversity and Ecosystem Health. https://www.epa.gov/report-environment/biodiversity-and-ecosystem-health [“Since few national programs track biodiversity and ecosystem health, ROE (Report on the Environment) indicators are available for only a limited set of ecosystem and population types. The substantial variation in ecological systems across geographic regions makes it difficult to develop national-scale biodiversity and ecosystem health indicators.”]

Congressional Research Service (July 8, 2021) In Focus: Biodiversity. [“The United States does not have a federal program to address biodiversity holistically, and there is no national biodiversity assessment for the United States.” “There are 196 parties to the CBD (United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity); the United States is not a party.”]

There is an enormous amount of misinformation, propaganda, and hyperbole available about cattle grazing in the U.S. due to vested interests, government support, history and tradition, and our affinity for beef. These sources include a subset of researchers and practitioners who idealize cattle grazing, theoretically claiming that it is widely beneficial for the land and can offset climate change in a range of biomes.[1-6]

We consider as “beef idealists” those who fail to acknowledge the overwhelming evidence of current pervasive degradation due to grazing as the starting point for discussions of “regenerative” practices. This misinformation is empowered by the lack of straightforward assessments from federal agencies.[7]

The impacts of grazing practices are varied, complex, site specific, and face dramatically changing conditions.[8] In the face of this complexity, researchers are hard pressed to make broad statements about damages.[9] Some grazing idealists use this complexity to sow confusion.

Finally, the centrality of cattle grazing in the history and culture of the West makes it an especially fraught subject.[10] Any clear documentation noting the degradation of grazing lands would be viewed unfavorably by a culture that claims grazing is both an inherent right and beneficial for the environment.[11]

Kansas Beef Council (2025) 6-12 STEM Education, Educational Resources for Youth, Exploring the Path of Beef Sustainability Reader Series. https://www.kansasbeef.org/more-information/beef-in-schools/6-12-stem-education

Teague, W. R., et al., (2016). The role of ruminants in reducing agriculture’s carbon footprint in North America. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, 71(2), 156-164, Abstract. [“We propose that with appropriate regenerative crop and grazing management, ruminants not only reduce overall GHG emissions, but also facilitate provision of essential ecosystem services, increase soil carbon (C) sequestration, and reduce environmental damage.”]

Grandin, T. (2022). Grazing cattle, sheep, and goats are important parts of a sustainable agricultural future. Animals, 12(16), 2092, p. 2. [“There is evidence that grazing can also be used to improve soil health and sequester carbon. Another sustainability benefit of well-managed grazing is increased plant biodiversity.” [italics added] From a researcher and practitioner with such extensive experience and deep understanding, one might expect an acknowledgement that there is much greater evidence that grazing as it is practiced consistently harms soil health. And that well-managed grazing is the exception, not the rule. And that the overwhelming evidence points to enormous environmental degradation due to grazing.]

Nicolette Hahn Niman (Dec. 19, 2014) Actually, Raising Beef Is Good for the Planet. Wall Street Journal. [“It’s that raising beef cattle, especially on grass, is an environmental gain for the planet.”]

Nordborg, M. (2016). Holistic management–a critical review of Allan Savory’s grazing method, p. 4. [“The claimed benefits of holistic grazing thus appear to be exaggerated and/or lack broad scientific support. Some claims concerning holistic grazing are directly at odds with scientific knowledge, e.g., the causes of land degradation and the relationship between cattle and atmospheric methane concentrations.”]

Carter, N. (November 2025). Regenerative Ranching vs. Rewilding – Evidence from 100+ studies analyzing better grazing vs. dietary change plant-based with rewilding. Institute for Future Food Systems. https://iffs.earth/living-report-regenerative-agriculture-vs-rewilding/ [See Section “Academic Tactics Used to Support Regenerative Grazing.”’

Bundy, L. R., et al., (2025). United States pasture and rangeland conditions: 1995–2022. Agronomy Journal, 117(1), e21736. [Note that this review and compilation of 28 years of USDA data was not undertaken by the USDA itself, but rather by a doctoral student and 2 professors. As they note, “to date, none have explored the comprehensive USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) general crop condition dataset, which consists of subjective weekly pasture and rangeland condition ratings by US state.” at p. 2.]

Copeland, S. M., et al., (2023). Variable effects of long‐term livestock grazing across the western United States suggest diverse approaches are needed to meet global change challenges. Applied Vegetation Science, 26(1), e12719, p. 11. [“The effects of grazing by wild and domesticated herbivores on rangeland ecosystem structure and function can vary widely, driven by the complex combinations of climate, soil type, natural disturbance regimes, plant communities, and historic and contemporary grazing practices… Despite such variation, livestock grazing effects are often described in simplistic, binary terms without acknowledging varying levels of impact or non-linear responses.”]

Charnley, S., et al., (2025). Managing for Flexibility on US Forest Service Grazing Allotments. Rangeland Ecology & Management, 101, 64-79. p. 66. [“There is no one-size-fits-all grazing management solution to improve rangeland conditions under current climate variability, or to withstand the locally specific impacts of climate change.]

Note: As all Americans know, cowboys and the open range are touchstones that romanticize individualism, exceptionalism, and resourcefulness. Criticizing grazing and pointing out the negative impacts is a cultural and political minefield that regularly exposes federal land management employees to “telephone threats to attempted murder” for doing their job. See, for example, GAO (2019) Federal Land Management Agencies: Additional Actions Needed to Address Facility Security Assessment Requirements.

This is reflected in the unusually low grazing fees on Western public lands, which are ~6% of the average cost of private grazing fees, see, Grazing on Federal Lands. And also reflected in the undocumented and unquantified amounts of unauthorized grazing on public lands, likely due to fear of retribution and the small number of enforcement officers. The BLM, for example, has one enforcement officer per 1.3 million acres. See, GAO (2016) Unauthorized Grazing: Actions Needed to Improve Tracking and Deterrence Efforts and GAO (2019) Additional Actions Needed to Address Facility Security Assessment Requirements, p. 29.

The net effect is to create a sense that there is “controversy” about whether grazing, as it is currently practiced, causes land degradation.[1]

There are 2 separate types of proselytizers about the potential positive impacts of so-called regenerative grazing.

There is one group that touts the benefits, while also acknowledging the significant challenges. They note the rare implementation of regenerative practices, the wide variations in methodology depending on climate and soil, and the damages from grazing as it is currently practiced on most operations.[2]

There is a second group that uses the possibility of using regenerative practices as an umbrella under which all grazing reaps a green halo. The theory appears to be “since grazing at a certain location, under certain conditions, using certain methodologies can possibly be beneficial for the environment, then all grazing is good, and all beef consumption is good.”[3]

The net effect has been to foster a belief that the impacts of grazing in the U.S. are a “controversial subject,” thereby offering a guilt-reducing patina to consumers of factory farmed meat.[4]

Lai, L., & Kumar, S. (2020). A global meta-analysis of livestock grazing impacts on soil properties. PloS one, 15(8), e0236638.,Abstract. [“Grazing effects on soil properties under different soil and environmental conditions across the globe are often controversial.”]

Will Harris (2023). A Bold Return to Giving a Damn: One Farm, Six Generations, and the Future of Food, Viking, ISNB 978-0593300473.

Nicolette Hahn Niman (Dec. 19, 2014) Actually, Raising Beef Is Good for the Planet, Wall Street Journal.

We use just these 2 examples though there are many researchers and practitioners in the first group and an entire industry and its lobbyists in the second.

Assuming (improbably) that the claims about enhancements to soil, land, and biodiversity from well-managed “regenerative” grazing are accurate, the methodology is rarely practiced in the real world. Beef idealists and promoters must ignore:

Lack of a market – So-called “grass-fed” beef products retail at more than double the costs of commodity beef.[1] The size of the market for domestic, labeled grass-fed beef is likely about 1% in the U.S.[2] An even smaller portion of that product is produced with the costly and labor-intensive techniques touted by beef idealists.[3]

Data about current damages – The actual data about on-the-ground damages is clear. Grazing is widely and credibly considered the largest single driver of land degradation globally.[4] U.S. federal agencies confirm high levels of land degradation due to current gazing practices (as noted throughout this page).

Increasing degradation – The sobering evidence confirms that arid lands, where most U.S. grazing occurs, are now undergoing increasing degradation due to climate change, wildfires, invasives, and recurring drought conditions.[5-7]

An unmanageable industry – U.S. cattle raising is an industry with about a half million operations.[8] There are no standard set of practices that can address the wide range of conditions and circumstances.[9,10] An aging population of producers increasingly feels economic pressure, is becoming less likely to value conservation, and is more likely to be grazing on lands they do not own.[11,12]

Grazing is one stage of factory farming – The purpose of grazing in the U.S. is to raise animals for factory farm feedlots. The environmental damages and abusive animal practices of feedlots are well documented. Idealistic claims about grazing rarely acknowledge this second production phase, ignoring the ultimate purpose of U.S. grazing systems.

USDA (June 2024) National Monthly Grass Fed Beef Report Agricultural Marketing Service. Calculates “grass-fed” retail pricing at 2 to 3 times the cost of “commodity beef.”]

Cheung, R., & McMahon, P. (2017). Back to grass: The market potential for US grassfed beef. Stone Barns Center for Food and Agriculture, pp. 5-6. [Although the share of “grass-fed” cattle is often estimated at about 4-5% this is not a believable figure, given the huge price differential. As this report notes, a) “imports account for an estimated 75-80% of total U.S. grassfed beef sales” and b) many of the so-called “grass-fed” cattle are “cull cows or bulls” that grazed their entire lives but were not raised to be, nor were marketed as, what is commonly understood to be “grass-fed beef.” We use this information to estimate the number of U.S. beef cattle raised as grass-fed at about 1% of total cattle.]

Gosnell, H., et al., (2020). Climate change mitigation as a co-benefit of regenerative ranching: insights from Australia and the United States. Interface focus, 10(5), 20200027. [“…many ranchers are extremely risk averse and only drawn to adopting practices that they are convinced will reduce their risk to stressors (increase adaptive capacity).”]

See, Global Land Degradation & Agriculture [question: “What are the primary drivers of land degradation?”]

Steinfeld, H., et al., (2019). Overview paper: Livestock, Climate and Natural Resource Use. FAO, p. 6. [“the effects of climate change on livestock… are expected to be most severe in arid and semi-arid grazing systems at low latitudes, where higher temperatures and lower rainfall is expected to reduce rangeland yields and increase degradation. Predicted changes in climate and weather are likely to result in more variable pasture productivity and quality, increased livestock heat stress, greater pest and weed effects, more frequent and longer droughts, more intense rainfall events, and greater risks of soil erosion.”]

Williams, A. P., et al., (2022). Rapid intensification of the emerging southwestern North American megadrought in 2020–2021. Nature Climate Change, 12(3), 232-234. [The period from “2000–2021 was the driest 22-yr period since at least 800.”]

Charnley, S., et al., (2025). Managing for Flexibility on US Forest Service Grazing Allotments. Rangeland Ecology & Management, 101, 64-79, Abstract. [“Many ranchers in the western U.S. operate in a rangeland environment characterized by seasonal and annual fluctuations in water and forage, recurring drought, spreading invasive plants, increased wildfire, warming temperatures, shifting grazing seasons, and predators. Climate change is predicted to exacerbate these characteristics.”]

USDA 2022 Census of Agriculture (2024), Table 12, p. 16. [“Beef cows” = ~622,000 farms. Counting those with 10 or more head in inventory = ~413,000]

Copeland, S. M., et al., (2023). Variable effects of long‐term livestock grazing across the western United States suggest diverse approaches are needed to meet global change challenges. Applied Vegetation Science, 26(1), e12719, p. 11. [“Best practices in the near future are more likely to be unique than shared across sites… will require adaptive grazing management reflective of the high complexity and variation across rangeland ecosystems.”]

Charnley, S., et al., (2025), p. 66. [“There is no one-size-fits-all grazing management solution to improve rangeland conditions under current climate variability, or to withstand the locally specific impacts of climate change.]

Raynor, E. J., et al., (2019). Shifting cattle producer beliefs on stocking and invasive forage: Implications for grassland conservation. Rangeland Ecology & Management, 72(6), 888-898, Abstract .[“First, a longitudinal evaluation of livestock producer demographics in 2007 and 2017 revealed individuals were older and were renting grazing land to a greater extent than in 2007. Second, when making land management decisions, producers in 2017 focused on economic concerns more than environmental concerns compared with more balanced views in 2007.”]

Bigelow, D., et al., (2016) U.S. Farmland Ownership, Tenure, and Transfer, USDA ERS, EIB-161, Figure 4, p. 7. [For cattle production, percentage of operated acres rented is ~43%]