Housing – Factory farmed pigs raised for meat spend most of their 6-month lives in large, enclosed finishing houses.[1] The houses are divided into rows of metal-fenced pens. A typical size shed is about 20,000 sq. ft. and holds 2,000 to 2,500 pigs. The houses generally have concrete slats as flooring so that excreta can fall or be flushed into manure pits below.[2,3]

Air quality – Pork producers use ventilation systems to counter the buildup of gases, particulate matter (PM), and airborne microorganisms in the finishing houses. Concentrated gases are commonly produced in the manure pits underneath the pens, including ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, and methane. The build-up of these gases, along with high concentrations of PM, cause respiratory illness in pigs as well as in workers. When levels of methane or hydrogen sulfide are high enough, they can quickly cause injuries or death.[4-6]

As of 2012, over 99% of pigs raised for meat were housed in facilities with no outside access.[7]

Pork Checkoff (2024) Life Cycle of a Market Pig. https://porkcheckoff.org/pork-branding/facts-statistics/life-cycle-of-a-market-pig/

[Pigs raised for meat live about 6 months – ~21 days “birth to weaning,” ~49 days in “nursery,” ~117 days in “growing and finishing” = 187 days or 26.7 weeks.]National Hog Farmer (2011). Designing ‘greener’ pig barns: Advisory group rethinks typical finishing barn design options. https://www.nationalhogfarmer.com/facilities-equipment/designing-greener-pig-barns-0919 [“Although fully slotted floors may be the preferred option… partially slotted floors are viewed as more welfare friendly…”]

Lammers, P. J. et al., (2023) Swine Housing Systems, Behavior, and Welfare. In Sustainable Swine Nutrition, 2nd Edition, Lee I. Chiba, (ed.), Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken, NJ., p. 615. [“Finishing barns almost always have concrete slats for flooring and metal gating to separate pens.”]

Ni, J. Q. et al., (2018). Ammonia and hydrogen sulfide in swine production. In Air quality and livestock farming, Banhazi, T., et al. (eds). London, UK: CRC Press: 29-47. 29(47), 9781315738338-3, p. 3.

National Pork Board (2018) Swine Care Handbook 2018, table 1, pp. 23-24.

Santana, C. M. et al., (2021). Ambient hydrogen sulfide exposure increases the severity of influenza A virus infection in swine. Archives of Environmental & Occupational Health, 76(8), 526–538.

USDA APHIS (2015), Swine 2012, Part I: Baseline Reference of Swine Health and Management in the United States, 2012, p. i. [“Over 99 percent of grower/finisher pigs were housed in facilities with no outside access.”]

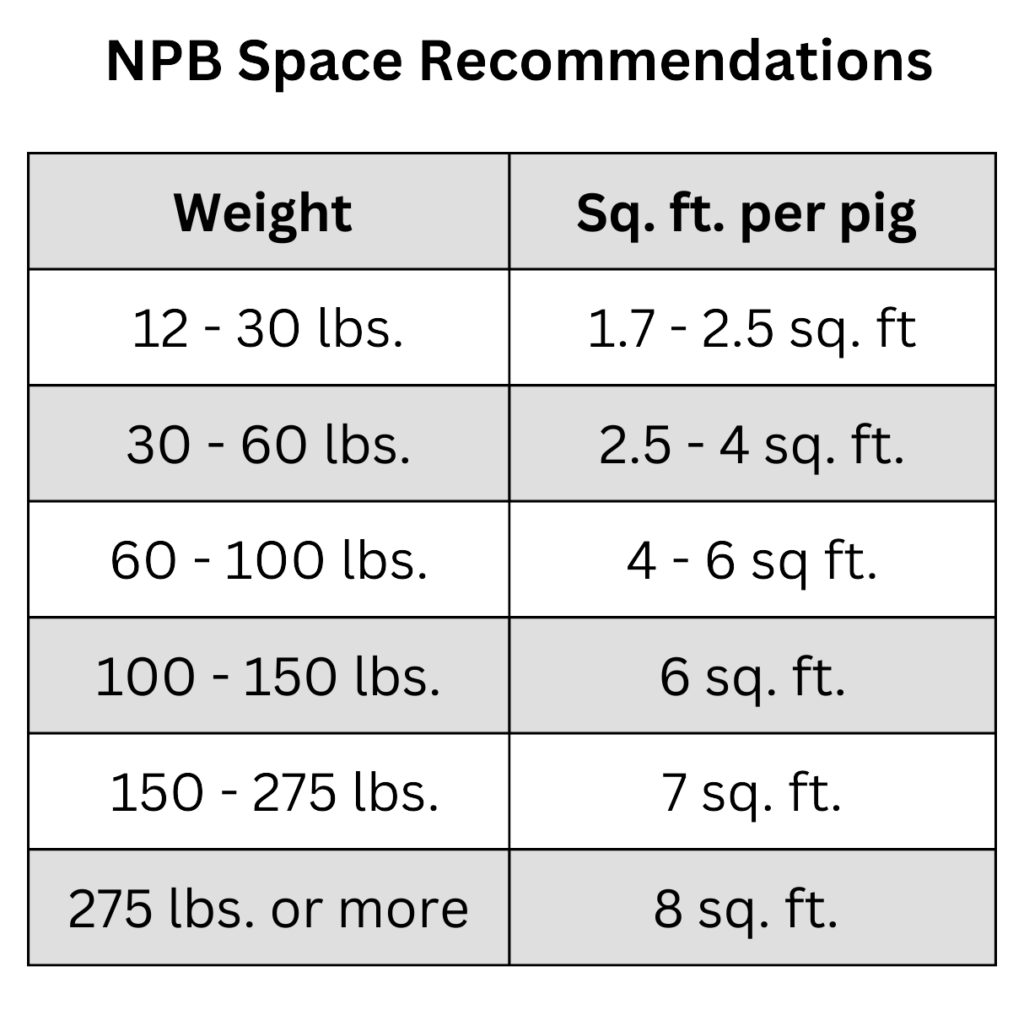

The National Pork Board (NPB) makes recommendations for floor space per pig based on weight:[1]

The average slaughter weight for pigs in 2023 was 287 pounds.[2] Typical space allocation on finishing farms is about 8 sq. ft. per pig (which is about 5’ long x 20” wide).[3,4] Most studies of space allocation focus on “growth performance and carcass characteristics,” with little or no mention of animal welfare.[5]

A pig that weighs about 290 pounds has an average length of about 4’ 3” and a width at the shoulders of 14” – a footprint of about 5 sq. ft. when standing.[6]

National Pork Board (2018) Swine Care Handbook 2018, table 1, p. 15.

USDA NASS (April 2024) Livestock Slaughter 2023 Summary, ISSN: 0499-0544, p. 15.

Michael Brumm, Univ. of Nebraska (2019). Space Allocation Decision for Nursery and Grow-Finish Facilities, U.S. Pork Center of Excellence/Cooperative Extension, p. 2. https://porkgateway.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/space-allocation-decisions-for-nursery-and-grow-finish-facilities.pdf [“Recent survey results suggest the average stocking density for finishing facilities in the US is 7.2 ft2/pig, with a range of 6.8 to 8.0 ft2/pig.”]

National Hog Farmer (2011). Designing ‘greener’ pig barns: Advisory group rethinks typical finishing barn design options. [“Providing 8 sq. ft./market hog is common…”]

Thomas, L. L. et al., (2017). Effects of space allocation on finishing pig growth performance and carcass characteristics. Translational Animal Science, 1(3), 351–357. https://doi.org/10.2527/tas2017.0042 [Comparing space allocations of 7, 8, and 9 sq. ft. per pig.]

Condotta, I. C. et al., (2018). Dimensions of the modern pig. Transactions of the ASABE, 61(5), 1729-1739, table 4, p. 1746.

Per pen: A common configuration is about 25 pigs raised in a pen sized 10’ by 19’ – or 190 sq. ft.[1] Comparatively, a small garage is about 240 sq. ft. Pens of different sizes may range up to 100 pigs, with 30 to 50 pigs per pen common configurations.[2-4]

Per house: Pig finishing operations typically have between 1,000 and 2,500 pigs per shed or house. A common size house (~20,000 sq. ft.) holds ~2,500 pigs.[5-7] A large shed can hold ~4,400 pigs,[8] which could be configured at 175 pens of around 25 pigs each.

Michael Brumm, Univ. of Nebraska (2019). Space Allocation Decision for Nursery and Grow-Finish Facilities, p. 3.

National Hog Farmer (2011). Designing ‘greener’ pig barns: Advisory group rethinks typical finishing barn design options. [“The number of pigs/pen is a matter of preference and available labor. Rates could be 16 to 100 pigs/pen, but the group agreed that 30 pigs/pen was most common and easiest to manage.”]

USDA APHIS (2011) Swine Industry Manual, FAD PreP, p. 13. [“Group sizes vary in grow‑finish facilities with pens commonly containing 30 to 50 animals.”]

Lammers, P. J. et al., (2023) Swine Housing Systems, Behavior, and Welfare. In Sustainable Swine Nutrition, 2nd Edition, Lee I. Chiba, (ed.), Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken, NJ., p. 615. [“Typical group size is approximately 20–30 grow-finish pigs per pen…”]

National Hog Farmer (2011). Designing ‘greener’ pig barns.

Betsy Freese (2018) Want to Contract Feed Pigs? Here’s What You Need to Know, Successful Farming. https://www.agriculture.com/livestock/hogs/want-to-contract-feed-pigs-heres-what-you-need-to-know

Michael Brumm (2019), Table 2.

Tom Bechman, Farm Progress (2018) See inside brand-new confinement hog barn. https://www.farmprogress.com/hog/see-inside-brand-new-confinement-hog-barn

Virtually all breeding sows live without outdoor access in large sheds that usually house thousands of other pigs.[1,2]

Inside the sheds, the most common living spaces are individual stalls, or crates. There are two types of crates, each slightly larger than a sow’s body. Once a young female pig (gilt) becomes pregnant the first time, she is moved to a gestation crate for about 4 months. Then, a few days before she gives birth, she is moved to a farrowing crate and remains there, with her piglets positioned slightly outside the crate, until they are weaned (about 3 weeks later). She is soon moved back to a gestation crate and is impregnated again.[3]

The flooring in these stalls is usually concrete with full-length or partial-length concrete slats so that excreta can fall or be flushed through to a manure pit below.[4] Both gestation and farrowing crates restrict almost all movement, social interaction with other sows, and the ability to perform any natural behaviors. A sow can stand up or lie down on her belly.

USDA APHIS (2015), Swine 2012, Part I: Baseline Reference of Swine Health and Management in the United States, 2012. [“Over 97 percent of sows and gilts housed in gestation facilities with no outside access…” at p. 28] [ “Almost all sows and gilts (98.9 percent) farrowed in facilities with no outside access. at p. 37.] Note: Gilts are breeding sows that have not yet been pregnant.

USDA (2024) 2022 Census of Agriculture, Table 25. [More than 95% of pigs on farrowing operations are on farms with over 2,000 pigs.]

Schuck-Paim, C., & Alonso, W. J. (2022). Productivity of mother pigs is lower, and mortality greater, in countries that still confine them in gestation crates [version 2; peer review: 2 approved]. F1000 Research, 11, 564, Figure 1. [Showing the typical lifecycle of a female pig used for breeding.]

Swine 2012, Part I: Baseline Reference of Swine Health and Management in the United States, 2012, pp. 29-30. [“For the 76.0 percent of breeding herds that used partially or completely slatted floors in the gestation phase, 98.0 percent used concrete for slatted flooring materials.”]

The housing stages for female pigs raised for breeding:

1) Piglets raised to be sows (like other piglets) are kept with their mothers in farrowing crates from birth until ~21 to 23 days of age.[1-3]

2) Weaned piglets (weaners) / gilts generally go to group pens until 6 to 7 months of age when they are impregnated.[4,5]

3) Gestating gilts (pregnant females that have not yet given birth) will spend about 115 days, or nearly 4 months in a gestation crate until about 3 days before giving birth.[6,7]

4) Sows (first parity) give birth in a farrowing crate and will nurse their piglets for ~21 days at which time the piglets are weaned (removed from the mother).

5) Weaned Sows (aka “open” sows) are typically moved to a gestation crate and impregnated again about 7 days after weaning.[8]

6) Sows (second parity) will then stay in the gestation crate for nearly 4 months, again able to either stand or lie on her belly.

And the cycle will continue until the sow is deemed no longer productive and is killed or sent to slaughter, according to the strict standards of factory farm profitability. A breeding sow produces on average ~2.2 litters per year.[9,10] Average life for sows is ~2 years with an average of ~3 parities at time of death or slaughter.[11,12]

USDA APHIS (2015), Swine 2012, Part I: Baseline Reference of Swine Health and Management in the United States, 2012, p. 50. [“For all pigs weaned, the average weaning age was 20.8 days.”]

Pork Checkoff (2024) Life Cycle of a Market Pig. [“Farrowing (birth to weaning) – 21 days – (3 weeks)”]

USDA APHIS (July 16, 2024) Swine Part I: Reference of Management Practices on Large-Enterprise Swine Operations in the U.S. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/swine-2021-part-i-reference-management-practices-large-enterprise-swine-operations-united-states [See: Individual Tables, Table B.5.a: Notes that “large operations” with >500 sows averaged 22.5 days, with smaller operations at ~ 28 days. Our assumption is that 90-95% of sows are on operations with >500 sows.]

USDA (2024) Hogs & Pork, Sector at a Glance, Hog Production. [“A gilt (a female hog that has not farrowed, i.e., given birth) typically reaches sufficient maturity to be bred at about 29 weeks of age.” 203 days or 6.7 months.]

Life Cycle of a Market Pig. [“Gilts (female pigs) reach maturity and are bred at 170 to 220 days of age.” (5.6 to 7.3 months)]

Life Cycle of a Market Pig. [“Gestation (pregnancy) 114 days. (3 months, 3 weeks and 3 days)”]

USDA (2024) Hogs & Pork, Sector at a Glance, Hog Production. [“…in approximately 3 months, 3 weeks, and 3 days, or 113 days (i.e., 16 weeks).”

USDA (2024) Hogs & Pork, Sector at a Glance, Hog Production. [“A sow (an adult female hog that has farrowed at least once) can be re-bred when the sow’s estrus cycle is re-established, which is typically about one week after weaning.”]

National Pork Board / Meta Farms (2022) Production Analysis Summary for U.S. Pork Industry: 2017-2021, p. 2 [For 2021: pigs weaned per mated female per year / pigs weaned per sow = 25.74 / 11.40 = 2.26]

PigCHAMP Knowledge Software, Benchmarking Summaries (USA 2023) https://www.pigchamp.com/benchmarking/benchmarking-summaries [Pigs weaned per female per year / pigs weaned per litter weaned = 2.24 (averaging 4 quarters)]

Swine Part I: Reference of Management Practices on Large-Enterprise Swine Operations in the U.S. [See: Individual Tables, Table B.6.a: Notes that “large operations” with >500 sows averaged 2.8 parities at culling or death, with smaller operations much higher and average of all sites at 3.0. For 3 parities, average life span is likely slightly under 2 years]

Hoge, M. D., & Bates, R. O. (2011). Developmental factors that influence sow longevity. Journal of Animal Science, 89(4), 1238-1245, Table 1. [Average parity of 3.5, average life of ~2.2 years. This is dated information; “unproductive” sows are presumably killed or slaughtered more quickly now.]

Gestation crates are typically 24”wide x 7’ long (14 sq. ft.), with railings about 40” high.[1,2] They are made of tubular metal with a feed trough and a drinking mechanism positioned at one end.

The body of a sow averages 16” in width and 5’ 7” in length standing up, with wide variance depending on their age, genotype, and stage of pregnancy. Lying down on her belly, the width of a sow commonly ranges from 17” to 28.5”.[3] Sows weigh on average about 500 pounds.[4,5]

John McGlone, Texas Tech Univ. (2013) Gestation Stall Design and Space: Care of Pregnant Sows in Individual Gestation Housing, National Pork Board, p. 2. [“A common gestation stall is 24 inches wide by 7 feet long.”]

Dr. Marchant-Forde, J. (2010) Housing and Welfare of Sows during Gestation, USDA Livestock Behavior Research Unit, p. 1. [“Stalls are typically constructed of tubular metal frames with a feed trough and drinker at the front, and are about 2.2 m long, 0.6 m wide and 1.0 m high…”]

John McGlone, Texas Tech Univ. (2013), p. 2.

McGlone, J. J., et al., (2004). The physical size of gestating sows. Journal of Animal Science, 82(8), 2421-2427, Table 2. [Average weight of sows at a group of studied operations was ~530 pounds.]

National Hog Farmer (October 15, 2013) Defining ideal sow body condition. [“The optimal sow weight in relation to number born alive was 500 lb. Sows that were substantially lighter or heavier than 500 lb. had a smaller litter size.”]

Broadly estimated, about 60% of gestating sows are kept in gestation crates throughout their pregnancies of about 115 days.[1] This is a change from 2012, when the USDA reported that ~76% of sows and gilts were confined in gestation crates.[2]

State initiatives and public sentiment are driving some producers to use group housing systems, though the long depreciation timeframe of housing systems may slow the transition away from gestation crates.

Ten states have passed laws restricting the use of gestation crates, though as of 2022, only ~3% of the national breeding herd was directly covered by these laws.[3] “By 2026, when all currently passed policies will have been fully implemented, less than 8% of the U.S. breeding hog inventory (at currently reported levels) will be covered by a gestation crate ban.”[4]

Moreover, some of the state “bans” on gestation crates simply prohibit conventionally sized gestation crates, permitting somewhat larger crates.[5,6] The recent California mandate requires minimum floorspace of 24 sq. ft. which is ~70% larger than the standard size gestation crate.[7]

USDA APHIS (July 16, 2024) Swine Part I: Reference of Management Practices on Large-Enterprise Swine Operations in the U.S. [See: Individual Tables, Table B.1.a: Notes that 61.3% of “large operations” with >500 sows use gestation crates and 57.5% of all operations with >100 sows. Our assumption is that 90-95% of sows are on operations with >500 sows.]

USDA APHIS (2015), Swine 2012, Part I: Baseline Reference of Swine Health and Management in the United States, 2012, p. 31. [“Just over three-fourths of all gestating sows and gilts (75.8 percent) were housed in individual stalls.” A “gestating gilt has not yet given birth and therefore is not referred to as a sow.”]

USDA ERS (2022) Hog welfare laws cover 9 states, 3% of national herd, https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/chart-gallery/gallery/chart-detail/?chartId=103505#

Pig333.com (April 28, 2023) Gestation crate bans will cover 10 states and 6% of U.S. swine herd by 2026. https://www.pig333.com/latest_swine_news/gestation-crate-bans-will-cover-6-of-u-s-swine-herd-by-2026_19280/

Danielle J. Ufer (2022), State Policies for Farm Animal Welfare in Production Practices of U.S. Livestock and Poultry Industries: An Overview, USDA Economic Research Service, Economic Information Bulletin No. 245, p. 5. [“Many States’ initial policies on confinement addressed behaviors, requiring that pregnant sows only be confined in ways that allow the animal to lie down, stand up, fully extend its limbs, and turn around freely.”]

See individual state ballot measures highlighted in the ASPCA’s Farm Animal Confinement Bans by State. https://www.aspca.org/improving-laws-animals/public-policy/farm-animal-confinement-bans

Cal. Code Regs. Title 3, § 1322.1 – Breeding Pig Confinement. [“An enclosure shall provide a minimum of 24 square feet of usable floorspace per breeding pig.”

A typical farrowing crate where a sow gives birth is about 6.5 to 7’ long by 24” wide by about 40” high, with some additional width at the base, so the sow can lie on her side.[1,2] They are similar in size and construction to gestation crates with the addition of an adjacent small pen in which piglets can lie and nurse. The farrowing crate has vertical metal bars running along the length to prevent the sow from rolling onto the piglets.

The number one cause of piglet pre-weaning mortality is generally considered “crushing by sow.”[3] But a report from the European Food Safety Authority that evaluated numerous studies of overall piglet mortality (excluding stillbirths) found that a substantial space increase for a sow actually reduces overall mortality because it reduces stress for the nursing sows and allows more interaction with their piglets. “For example, cold stress and prolonged hunger, piglet vitality and birth weight, as well sow maternal behaviour, play an important role on piglets survival.”[4]

Lammers, P. J. et al., (2023) Swine Housing Systems, Behavior, and Welfare. In Sustainable Swine Nutrition, 2nd Edition, Lee I. Chiba, (ed.), Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken, NJ., p. 610. [“Traditional farrowing stall (2.0 × 0.61 m)” = 79”L x 24”W]

Dr. Marchant-Forde, J. (ed.) (2009) The Welfare of Pigs, USDA Agricultural Research Service, Springer, West Lafayette, IN, p. 147. [The standard farrowing crate is usually a tubular metal construction fixed within a pen of about 2.2 m x 1.5 m, with recommended dimensions of around 2.2 m long, 0.6 m wide and 1.0 m high.” Entire pen = 87”L x 59”W and sow’s space = 87”L x 24”W x 39”H with some additional width at the base so the sow can lie on her side.]

USDA APHIS (2015), Swine 2012, Part I: Baseline Reference of Swine Health and Management in the United States, 2012, p. 48. [Crushing by sow causes 49% of pre-weaning deaths.]

European Food Safety Authority (2022) Welfare of pigs on a farm, EFSA Journal, Scientific Opinion, p. 76. [the conventional farrowing crate (in the U.S. of ~14 sq ft.) was compared to some European farrowing pens that ranged from 70 to 86 sq ft.]

More than 80% of nursing sows farrow their piglets in farrowing crates.[1] In 2015, the USDA reported that ~99% of nursing sows were kept in farrowing crates.[2]

USDA APHIS (July 16, 2024) Swine Part I: Reference of Management Practices on Large-Enterprise Swine Operations in the U.S. [See: Individual Tables, Table B.1.c: Notes that 84% of “large operations” with >500 sows use farrowing crates (referred to as “individual stalls or crates”), 60.7% of “medium operations” and 82.9% of all operations. Our assumption is that 90-95% of sows are on operations with >500 sows.]

USDA APHIS (2015), Swine 2012, Part I: Baseline Reference of Swine Health and Management in the United States, 2012, p. 40. [“Nearly all sows and gilts (98.6 percent) farrowed in individual housing.”]

In some operations, sows are housed in group settings for all or part of gestation and farrowing. Group housing allows for some movement and interaction with pen-mates.

National Pork Producers states that gestating sows are generally allotted 16-18 sq. ft. per sow in group housing.[1-2]

At 17 sq. ft per sow, 14 pigs would live in a space the size of a small garage (12’ x 20’). The weight of the sows would equal the weight of 40 humans.[3]

National Pork Producers Council v. Karen Ross, Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the U.S. Court of Appeals, 9th Cir. (2021), p. 8. [“The remaining 28% of farmers keep their sows most of the time in group pens, which generally provide 16 to 18 square feet of space per sow.”]

Gonyou, H. et al., (2013) Group Housing Systems: Floor Space Allowance and Group Size, National Pork Board, p. 2. [These previous recommendations were “19-24 sq ft for mature sows…”]

McGlone, J. J., et al., (2004). The physical size of gestating sows. Journal of Animal Science, 82(8), 2421-2427, Table 2. [Assuming average sow weight at 530 pounds as noted here, and average human weight at 185 pounds.]

Anyone who understands even the bare minimum about these animal imprisonment systems can see that sows are some of the most mis-treated beings on earth. And yet the conditions outlined on this page are only a part of the mistreatment, which includes un-anesthetized tail removals, teeth cutting, ear notchings, invasive artificial inseminations, living daily amidst their own waste, and breathing polluted air.

Pigs are highly complex animals, both behaviorally and cognitively.[1] An Iowa State Univ. report that aims to help farm workers with the “handling and restraint” of pigs offers these points (among others) about their behavior:[2] “Swine are gregarious and social animals. They have a natural tendency to follow each other and maintain visual or body contact. Isolation from a social group is very stressful for pigs.”

“Swine have an inquisitive nature and spend much of their time in forage-related activities, such as rooting, grazing and exploring with their snout.”

“Pigs have a strong natural urge to escape. Small gaps between pens, alleys, ramps, side gates, chutes, may encourage a pig to escape. During these escape attempts, pigs frequently injure themselves.”

Many sows in gestation crates cannot comfortably lie down, even in a prone position (on their bellies) because their bodies are too wide. One group of researchers found that “most gestation stalls are not wide enough to allow sows to be contained within the width of the stall while lying down.”[3] Even the National Pork Board acknowledges, “Conventional gestation stalls may not be wide enough for larger sows to lie laterally, especially towards the end of gestation.”[4]

Gestation crates in commercial hog production systems are specifically designed so the sow cannot turn around. This activity is considered problematic for management because females that turn around may defecate in the feeder or in other places hard to flush out, or they may try to jump out of the stall on the rear side where the fencing is often lower.[5]

Gestation crates “are linked to several welfare and health problems, such as pressure sores, ulcers, and abrasions, poorer cardiac function and immune-competence and a greater frequency of stereotypic behaviors.”[6] Some of the abnormal behaviors exhibited include continuous chewing with no feed in the mouth, chewing the metal bars of the crate for extended periods, head-weaving, and pressing drinkers without drinking. Apathetic behavior, akin to severe clinical depression in humans, is also noted.[7]

Group housing during gestation, though an improvement over gestation crates, is a lesser form of torturous confinement with a slightly different group of welfare challenges.[8]

Animal Welfare Institute (June 5, 2024), Comment on AVMA’s Policy on “Pregnant Sow Housing.” pp. 3-4. [This well-documented comment to the American Veterinary Medical Association provides an overview of the research on pig behavior, abilities, and social proclivities.]

Center for Food Security, Iowa State Univ. (2014) Animal Behavior and Restraint: Swine. https://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/Emergency-Response/Just-in-Time/08-Animal-Behavior-Restraint-Swine-HANDOUT.pdf

McGlone, J.J. et al., (2004). Physical size of gestating sows. Journal of Animal Science, 82(8), 2421–2427, p. 2425.

National Pork Board (2018) Swine Care Handbook 2018, p. 14.

Jay Harmon & Donald Lewis (2006) Sow housing options for gestation, factsheet, Pork Information Gateway, p. 7.

Schuck-Paim, C., & Alonso, W. J. (2022). Productivity of mother pigs is lower, and mortality greater, in countries that still confine them in gestation crates [version 2; peer review: 2 approved]. F1000 Research, 11, 564, p. 3.

Animal Welfare Institute (June 5, 2024), pp. 4-10.

Animal Welfare Institute (June 5, 2024), pp. 10-13.