The model can be simply stated: use genetics, drugs, and production techniques to maximize the number of slaughter-bound pigs per inventoried sow, while allocating the least amount of space, feed, and labor.[1-3] The deaths of piglets and sows and their suffering is not in the equation, as long as total pounds of meat divided by cost of inputs is growing.

To achieve maximum “efficiency” the industry sets certain benchmarks that center on the total number of weaned piglets a sow can produce in a year.[4] The key figures are:

Number of piglets per litter.

Number still alive after weaning.

Number of litters per sow per year.

A female pig who does not meet the benchmarks is culled or “removed” from the herd and sent to slaughter. In 2024, the average cull rate was ~46%.[5]

Bradley Eckberg (2024) Maximizing pork production: Importance of a quality breed target. National Hog Farmer. [“At the heart of every pork production operation lies the goal of economic efficiency. Maximizing profits while minimizing costs is the ultimate objective. Different swine genetics possess unique characteristics that can significantly impact production economics. Factors such as growth rates, feed conversion ratios, and meat quality attributes play pivotal roles in determining profitability.”]

Maes, D., et al., (2019) A critical reflection on intensive pork production with an emphasis on animal health and welfare. Journal of Animal Science, Vol. 98, No, Suppl. 1, p. S-15. [“Intensive pig production is characterized by a high biological and economic productivity with a simultaneously low input of labor, feed, and space per animal. As a rule, this results in bigger herds with a large number of livestock indoors, specialization, and standardized management procedures within a farm.”]

USDA ERS (2022) U.S. Hog Production: Rising Output and Changing Trends in Productivity Growth, ERR-308, p. 4 & 16. [“Between 1992 and 2015, hog production became more efficient. Inflation-adjusted (real) production costs per hundredweight declined continuously over the period and by 2015 were 41 percent of those incurred in 1992.” “Labor use on hog farms declined by 83 percent between 1992 and 2015, as the number of hours required to produce 100 pounds of weight gain shrank from 1.2 hours to 0.2 hours.”]

Michael Langemeier (2024) Long-Term Trends in Pigs Per Litter. Farm Journal’s Pork. [“Key performance metrics for swine production include feed conversion, litters per sow per year, pigs per litter, and pounds of pork produced per sow per year.”]

PigCHAMP Knowledge Software, Benchmarking Summaries (North America 2024 year summary) https://www.pigchamp.com/benchmarking/benchmarking-summaries [Culling rate = 45.58%. Culling rate does not include “death rate” which is “died or euthanized.” Culling rate plus death rate = sows removed from herd, which tends to average ~55-60% per year.]

Factory farms specializing in pig reproduction range in size, with larger operations at 10,000 to 12,000 sows.[1-3] Units with more than 5,000 sows are common.[4,5]

Bradley Eckberg (August 28, 2024) U.S. sow farm production update. National Hog Farmer. [“The average sow farm size was 2,583, with the smallest farm size of 500 females and the largest at 11,000 females.” This refers to a study of ~300 U.S. farms.]

Farm Journal’s Pork (January 26, 2023) First All-Steel Swine Barns Under Construction in South Dakota. [“A new 12,000-sow complex is under construction in South Dakota that features the first prefabricated steel swine barns in the U.S.”]

Ross, J. W. (2019) Identification of putative factors contributing to pelvic organ prolapse in sows. Iowa State University, Table 1, p. 5. [Maximum sows on operation = 10,606. Average = 3,713. Study was of 104 farms from 15 U.S. states.]

Betsy Freese (April 17, 2017) New Sow Barns for Iowa Select Farms. Successful Farming. [“Three more sow farms are coming, all larger – at 7,500 sows – than this one.”]

Mindy Ward (June 8, 2017) Take a peek inside a 5,500-sow unit. National Hog Farmer.

The total inventory of breeding pigs is about 6 million in 2025.[1] Almost all are sows and gilts (female pigs who have not yet given birth), with a very small number of boars, likely less than 1% of the total.[2]

USDA NASS (June 1, 2025) Quarterly Hogs and Pigs Inventory. [“Of the 75.1 million hogs and pigs, 69.2 million were market hogs, while 5.98 million were kept for breeding.” This is “a point in time estimate as of the reference date of swine inventory.”]

Phil Burke (2020) The Evolution of Swine Artificial Insemination, PigCHAMP Benchmark Magazine. [“By the millennium, AI (artificial insemination) was used on more than 99% of all sows inseminated, over 35,000 boars were housed in 200+ studs in the US. The days of having 400,000 natural service boars on farm were over.”]

The housing stages for a female pig raised for breeding:

1) Piglets raised to be sows (like other piglets) are kept with their mothers in farrowing crates from birth until ~21-23 days of age.[1,2]

2) Weaned piglets (weaners) / gilts generally go to group pens until 6 to 7 months of age when they are impregnated.[3,4]

3) Gestating gilts (pregnant females that have not yet given birth) will spend about 115 days, or nearly 4 months in a gestation crate until about 3 days before giving birth.[5]

4) Sows (first parity) give birth in a farrowing crate and will nurse their piglets for ~21 days at which time the piglets are weaned (removed from the mother).[6]

5) Weaned Sows (aka “open” sows) are typically moved to a gestation crate and impregnated again about 7 days after weaning.[7]

6) Sows (second parity) will again stay in the gestation crate for nearly 4 months, able only to stand or lie on her belly (not on her side).

And the cycle will continue until the sow dies or is deemed no longer productive and is killed or sent to slaughter, according to the standards of factory farm profitability.

Pork Checkoff (2024) Life Cycle of a Market Pig. [“Farrowing (birth to weaning) – 21 days (3 weeks)”] https://porkcheckoff.org/pork-branding/facts-statistics/life-cycle-of-a-market-pig/

USDA APHIS (July 16, 2024) Swine Part I: Reference of Management Practices on Large-Enterprise Swine Operations in the U.S. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/swine-2021-part-i-reference-management-practices-large-enterprise-swine-operations-united-states [See: Individual Tables, Table B.5.a. noting that “large operations” with >500 sows averaged 22.5 days, with smaller operations at ~28 days. Our assumption is that 90-95% of sows are on operations with >500 sows.]

USDA (updated 2025) Hogs & Pork, Sector at a Glance, Hog Production. [“A gilt (a female hog that has not farrowed, i.e., given birth) typically reaches sufficient maturity to be bred at about 29 weeks of age.” 203 days or 6.7 months.]

Pork Checkoff (2024) Life Cycle of a Market Pig. [“Gilts (female pigs) reach maturity and are bred at 170 to 220 days of age.” 5.6 to 7.3 months.]

Pork Checkoff (2024) Life Cycle of a Market Pig. [Gestation = 114 days or 3 months, 3 weeks and 3 days] and USDA (2025) Hogs & Pork, Sector at a Glance, Hog Production. [“…in approximately 3 months, 3 weeks, and 3 days, or 113 days (i.e., 16 weeks).”]

Pork Checkoff (2024) Life Cycle of a Market Pig. [Farrowing = 21 days]

USDA (2025) Hogs & Pork, Sector at a Glance, Hog Production. [“A sow (an adult female hog that has farrowed at least once) can be re-bred when the sow’s estrus cycle is re-established, which is typically about one week after weaning.”]

On average, factory farmed sows live a little under 2 years; they die or are culled after 3 parities.[1-3] Each year, about 55-60% of the sow herd dies or is culled.[4,5]

If a breeding sow survives for a full year, she produces on average about 2 litters in that year.[6-8]

The natural lifespan of a domesticated pig is 12-15 years.[9]

USDA APHIS (2024) Swine Part I: Reference of Management Practices on Large-Enterprise Swine Operations in the U.S., Breeding Management. [See: Individual Tables, Table B.6.a. Notes that “large operations” with >500 sows averaged 2.8 parities at culling or death, with smaller operations much higher and average of all sites at 3.0. For 3 parities, we calculate that average life span is likely slightly under 2 years.]

Erin L. Schenck et al., (2010) Sow Lameness and Longevity, Fact Sheet. USDA Agricultural Research Service. [“The average parity at culling is 3 (approximately 23 months of age).” Few references mention age at culling, focusing instead on number of parities.]

Hoge, M. D., & Bates, R. O. (2011). Developmental factors that influence sow longevity. Journal of Animal Science, 89(4), 1238-1245, Table 1. [Average parity of 3.5, average life of ~2.2 years. This is dated information; “unproductive” sows are presumably killed or slaughtered more quickly now.]

PigCHAMP Knowledge Software, Benchmarking Summaries (USA & Canada 2024 year summary) [Culling rate = 45.6% + 12.5% death rate = ~58% total]

National Pork Board, Meta Farms (2024) Production Analysis Summary for U.S. Pork Industry: 2019-2023, p. 8. [For 2021-2023: “Replacement rate” at ~57%. Replacements typically = approximately culling plus death rate.]

USDA APHIS (July 16, 2024) Swine Part I: Reference of Management Practices on Large-Enterprise Swine Operations in the U.S. See: Individual Tables, Table B.4.b. [Medium and Large operations (> 250 and >500 sows) have .9 litters per 6-month period, or 1.8 per year.]

National Pork Board, Meta Farms (2024) Production Analysis Summary for U.S. Pork Industry: 2019-2023, p. 2. [For 2021-2023: pigs weaned per mated female per year / pigs weaned per sow = 25.88 / 11.45 = 2.26]

PigCHAMP Knowledge Software, Benchmarking Summaries (USA 2024 year summary) [Pigs weaned per female per year / pigs weaned per litter weaned = 2.19 (averaging 4 quarters)]

Kenneth Stalder et al., (2006) Longevity in Breeding Animals, in Diseases of Swine, (Zimmerman, J.J., et al. eds.) 10th ed., p. 51. [Sows are removed from breeding herds at a very young age considering that the “natural” longevity would most likely be 12–15 years.”]

Gestation crates are typically 24”wide x 7’ long (14 sq. ft.), with railings about 40” high.[1-3] They are made of tubular metal with a feed trough and a drinking mechanism positioned at one end.

The body of a sow averages 16” in width and 5’ 7” in length standing up, with wide variance depending on their age, genotype, and stage of pregnancy. Lying down on her belly, the width of a sow commonly ranges from 17” to 28.5”.[4] Sows weigh on average about 500 pounds.[5,6]

Broadly estimated, about 60% of gestating sows are kept in gestation crates through their pregnancies of about 115 days.[7]

John McGlone, Texas Tech Univ. (2013) Gestation Stall Design and Space: Care of Pregnant Sows in Individual Gestation Housing, National Pork Board, p. 2. [“A common gestation stall is 24 inches wide by 7 feet long.”]

Dr. Marchant-Forde, J. (2010) Housing and Welfare of Sows during Gestation, USDA Livestock Behavior Research Unit, p. 1. [“Stalls are typically constructed of tubular metal frames with a feed trough and drinker at the front, and are about 2.2 m long, 0.6 m wide and 1.0 m high…”]

See also, Pig Housing Conditions and Space Allotments.

John McGlone (2013), p. 2.

McGlone, J. J., et al., (2004). The physical size of gestating sows. Journal of Animal Science, 82(8), 2421-2427, Table 2. [Average weight of sows in a group of studied operations was ~530 pounds. Sows tend to get heavier with each parity.]

National Hog Farmer (October 15, 2013) Defining ideal sow body condition. [“The optimal sow weight in relation to number born alive was 500 lb. Sows that were substantially lighter or heavier than 500 lb. had a smaller litter size.”]

USDA APHIS (2024) Swine Part I: Reference of Management Practices on Large-Enterprise Swine Operations in the U.S., Breeding Management. [See: Individual Tables, Table B.1.a. (Notes that 61.3% of “large operations” with >500 sows use gestation crates and 57.5% of all operations with >100 sows. Our assumption is that 90-95% of sows are on operations with >500 sows.)]

A typical farrowing crate where a sow gives birth is ~6.5 to 7’ long by 24” wide by about 40” high, with some additional width at the base, so the sow can lie on her side.[1,2] They are similar in size and construction to gestation crates with the addition of an adjacent small pen in which piglets can lie and nurse.

The farrowing crate has vertical metal bars running along the length to restrict the sow from rolling onto the piglets.[3] However, it does not prevent all mortality due to movement of the sow, especially for piglets born at low weights.[4]

More than 80% of sows in the U.S. are kept in farrowing crates.[5]

Lammers, P. J., et al., (2023) Swine Housing Systems, Behavior, and Welfare, in Sustainable Swine Nutrition, 2nd Edition, Lee I. Chiba (ed.), Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken, NJ., p. 610. [“Traditional farrowing stall (2.0 × 0.61 m)” = 79”L x 24”W]

Dr. Marchant-Forde, J. (ed.) (2009) The Welfare of Pigs, USDA Agricultural Research Service, Springer, West Lafayette, IN, p. 147. [The standard farrowing crate is usually a tubular metal construction fixed within a pen of about 2.2 m x 1.5 m, with recommended dimensions of around 2.2 m long, 0.6 m wide and 1.0 m high.” Entire pen = 87”L x 59”W and sow’s space = 87”L x 24”W x 39”H with some additional width at the base so the sow can lie on her side.]

USDA APHIS (2015), Swine 2012, Part I: Baseline Reference of Swine Health and Management in the United States, 2012, p. 48. [Crushing by sow causes 49% of pre-weaning deaths.]

Nicolaisen, T., et al, (2019) The Effect of Sows’ and Piglets’ Behaviour on Piglet Crushing Patterns in Two Different Farrowing Pen Systems. Animals, 9, 538, p. 2 and Table 1, p. 7.

USDA APHIS (2024) Swine Part I: Reference of Management Practices on Large-Enterprise Swine Operations in the U.S., Breeding Management. Confinement Types – B. 1. c. [Farrowing Crates: 84.0% of large operations (>500 sows) and 82.9% of all sites.]

More than 99% of sows are regularly subjected to artificial insemination.[1] A two-foot long plastic catheter is inserted into or past the cervix.[2] Rates of injury and bleeding are studied, generally to determine if reproduction rates are affected.[3,4]

While restrained in a gestation crate, a sow is forcibly inseminated usually once per day during her 2-3 day estrus period.[5,6] A more recent procedure known as post-cervical artificial insemination (PCAI) is used on about half of U.S. sows, where the catheter is inserted about 7 inches past the cervix and directly into the sow’s uterus.[7,8] This causes higher rates of injury and bleeding.[9,10]

Subjecting pigs to these abuses would run afoul of anti-bestiality statutes in many states if not for the regulatory exemptions for factory farmed animals.[11]

USDA APHIS (2024) Swine Part I: Reference of Management Practices on Large-Enterprise Swine Operations in the U.S., Breeding Management. Breeding Methods – B. 3. b. [Artificial Insemination: 99.7%.]

García-Vázquez, F. A., et al., (2019). Post-cervical artificial insemination in porcine: The technique that came to stay. Theriogenology, 129, 37-45. p. 37. [“In general terms, the devices consist of a tube (~50-60 cm length)…”]

Sbardella, P. E., et al., (2014). The post‐cervical insemination does not impair the reproductive performance of primiparous sows. Reproduction in domestic animals, 49(1), 59-64. p. 61 & 63. [“Fewer CAI sows (2.4%; 4/165) bled during insemination (P0.0001) compared with PCAI sows (23%; 28/165).” “However, reproductive performance is not always affected by bleeding during PCAI insemination.”]

García-Vázquez, F. A., et al., (2019), p. 38. [“In this respect, genital tract injury or bleeding, during PCAI application has been associated with the insertion of the cannula through the cervix … Some studies have observed detrimental effects on reproductive performance in cases of bleeding during PCAI, although other studies found no association of bleeding with a negative impact on reproductive performance … traumatic injury and bleeding seem to be commonly observed when force is applied to pass the resistance point during the introduction of the cannula.”]

Knox, R. V. (2016). Artificial insemination in pigs today. Theriogenology, 85(1), 83-93, p. 88. [“Although most sows will receive two AI doses, one for each day detected in standing estrus, a smaller proportion of sows may only receive one dose or up to three doses, on the basis of shorter and longer duration of estrus, respectively… Estrus usually lasts 45 to 65 hours”]

J. Sterle & T. Sanfranski (2018) Artificial Insemination in Swine: Breeding the Female. Univ. of Missouri Extension. [“Additionally, it is recommended that all females be mated once daily each day they stand.”]

Phil Burke (2020) The Evolution of Swine Artificial Insemination. PigCHAMP Benchmark Magazine. [“In 2020, PCAI will exceed 50% utilization for the first time in the USA.”]

García-Vázquez, F. A., et al., (2019), p. 37. [“This method consists of depositing the semen dose in the uterine body through an inner tube/cannula inserted in the catheter (reaching 15-20 cm [7 inches] deeper than CAI).”]

Sbardella, P. E., et al., (2014), p. 61. [“Fewer CAI sows (2.4%; 4/165) bled during insemination (P0.0001) compared with PCAI sows (23%; 28/165).”

García-Vázquez, F. A., et al., (2019), p. 38. [“In this respect, genital tract injury or bleeding, during PCAI application has been associated with the insertion of the cannula through the cervix. The occurrence of bleeding is lower in multiparous (~2-9%) than in primiparous and nulliparous females (15-23%).”]

Gabriel N. Rosenberg & Jan Dutkiewicz (December 11, 2020) The Meat Industry’s Bestiality Problem. The New Republic.

On average, in 2024, the number of piglets:[1-4]

Conceived is ~16 piglets.

Born alive is ~14 piglets.[5,6]

Weaned is ~12 piglets.

Litters of 18-20 piglets are not uncommon.[7,8] On average, female pigs have about 14 functional teats.[9-11]

PigCHAMP Knowledge Software, Benchmarking Summaries. North America 2024 year end summary, Average total pigs per litter, mean = 15.96, less stillborn and mummified (1.69) = 14.27 born alive, less pre-wean mortality = 12.47 piglets weaned. Note: The PigChamp 2024 summary includes Canadian farms.]

National Pork Board, Meta Farms (2025) Production Analysis Summary for U.S. Pork Industry: 2020-2024, p. 3. [For 2024: Born alive = 14.28, Weaned per sow farrowed = 11.92]

USDA APHIS (2024) Swine Part I: Reference of Management Practices on Large-Enterprise Swine Operations in the U.S., Breeding Management. Farrowing Productivity – B.4.c. [In large operations (>500) Born = 14.7, Born alive = 13.6, Weaned = 11.5]

USDA NASS (September 25, 2025) Quarterly Hogs and Pigs, ISSN: 1949-1921, p. 5. [Total 2024 “pigs saved per litter” is 11.68. This includes post-weaning pig death and is therefore very close to Pigchamp figure of 12.47 (see, footnote 1)]

“Born alive” excludes stillborns and mummies. Stillborn is a fully developed piglet that is alive before the onset of farrowing and dies during the farrowing process without ever taking a breath. [Pig333.com (n.d.) Pig Glossary “Stillborn piglet.”]

“Mummies” refers to those who have died during the pregnancy. [Pig333.com (n.d.) Pig Glossary “Mummified piglets”]

Oliviero, C., et al., (2019) The challenge of large litters on the immune system of the sow and the piglets. Reproduction in Domestic Animals, vol. 54, no. 53, p. 12. [“Nowadays, when raising hyperprolific sow lines, it is not uncommon to have litters up to 18–20 piglets.”]

Baxter, E.M., et al., (2013) The welfare implications of large litter size in the domestic pig II: management factors. Animal Welfare Journal, vol. 22, no. 2, p. 220 [“Litter sizes between 14 and 20 can be classified as ‘large’, and litters of 21 or above as ‘very large’.”]

Earnhardt-San, A. L., et al., (2023). Genetic parameter estimates for teat and mammary traits in commercial sows. Animals, 13(15), 2400. Abstract [Functioning teats = 13.90]

Wiegert, J. G., & Knauer, M. T. (2018). Sow Functional Teat Number Impacts Colostrum Intake and Piglet Throughput. Journal of Animal Science, 96 (suppl_2), 51-52. [Average functional teat number was 14.83]

The Pig Site (November 9, 2018) The Udder. [“The ideal would be 16 teats, but this may represent only 5% of the gilt population, with around only 25% having 14 – so the commercial choice is 12 good teats with 14 or 16 in the Meishan cross breed. If however, you are selecting gilts from your own herd, select 14 or more if possible.”]

In the last 20 years, average litter size has increased by ~4 piglets per litter.[1,2] Genetic breeding has driven the trend.[3]

Researchers calculate a 74% increase in overall meat production per sow since 1994. This has been accomplished by increasing the number of sows by ~5% while pounds of meat production per sow increased ~80%.[4]

PigCHAMP Knowledge Software, Benchmarking Summaries. 2024 year-end summary, Average total pigs per litter, mean = 15.96]

PigCHAMP Knowledge Software, Benchmarking Summaries. Year-end summaries from 2004-2024.

Ward, S. A., et al., (2020) Are Larger Litters a Concern for Piglet Survival or An Effectively Manageable Trait? Animals, 10,309, p. 1 [“In the swine industry, sows are selectively bred for larger litters so, theoretically, more pigs can be sold per year.”]

Michael Langemeier (November 12, 2024) Long-Term Trends in Pigs per Litter. Purdue Univ. Center for Commercial Agriculture.

Litter sizes and sow mortality have both trended rapidly upwards in the last 20 years. Although it is obvious that larger litters add to the stress levels for sows,[1] many researchers steadfastly look elsewhere for the reasons sow mortality is increasing, presumably because larger litter sizes are non-negotiable for economic reasons.[2,3]

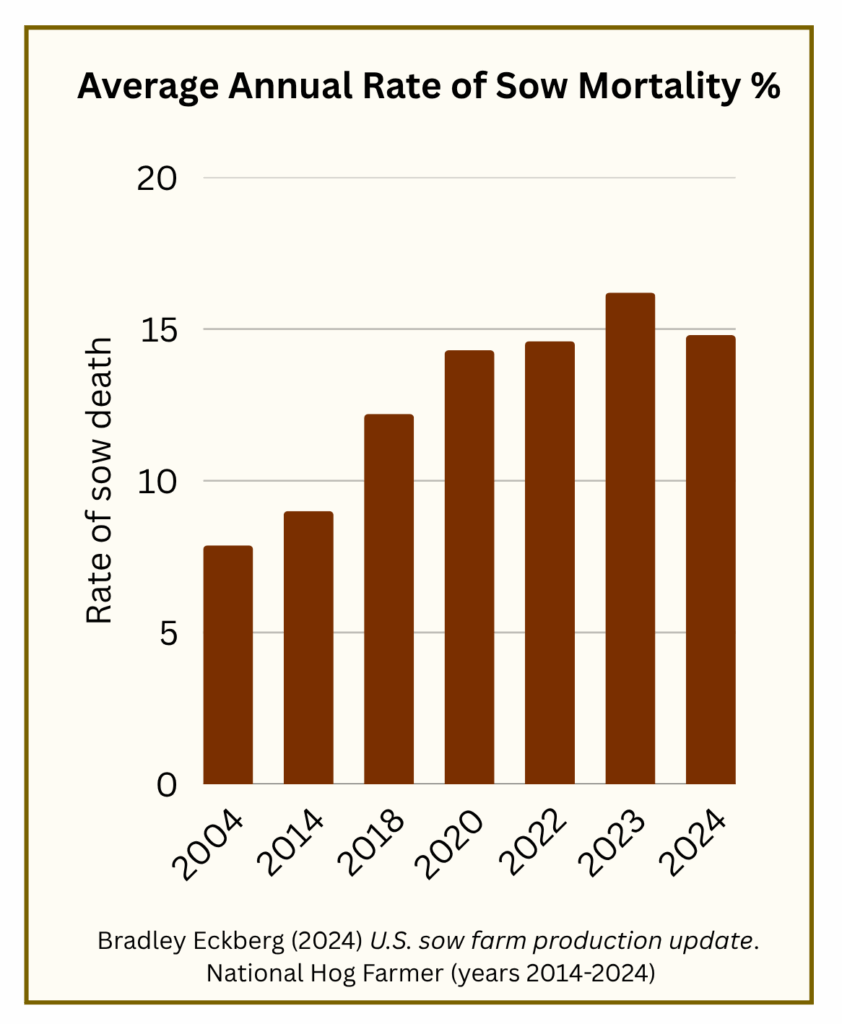

Sow mortality – In the last 20 years, the rate of sow mortality has nearly doubled, from ~8% in 2004 to ~15% in 2024.[4,5] Deaths tend to peak between one and ten days postpartum and during the prepartum phase.[6]

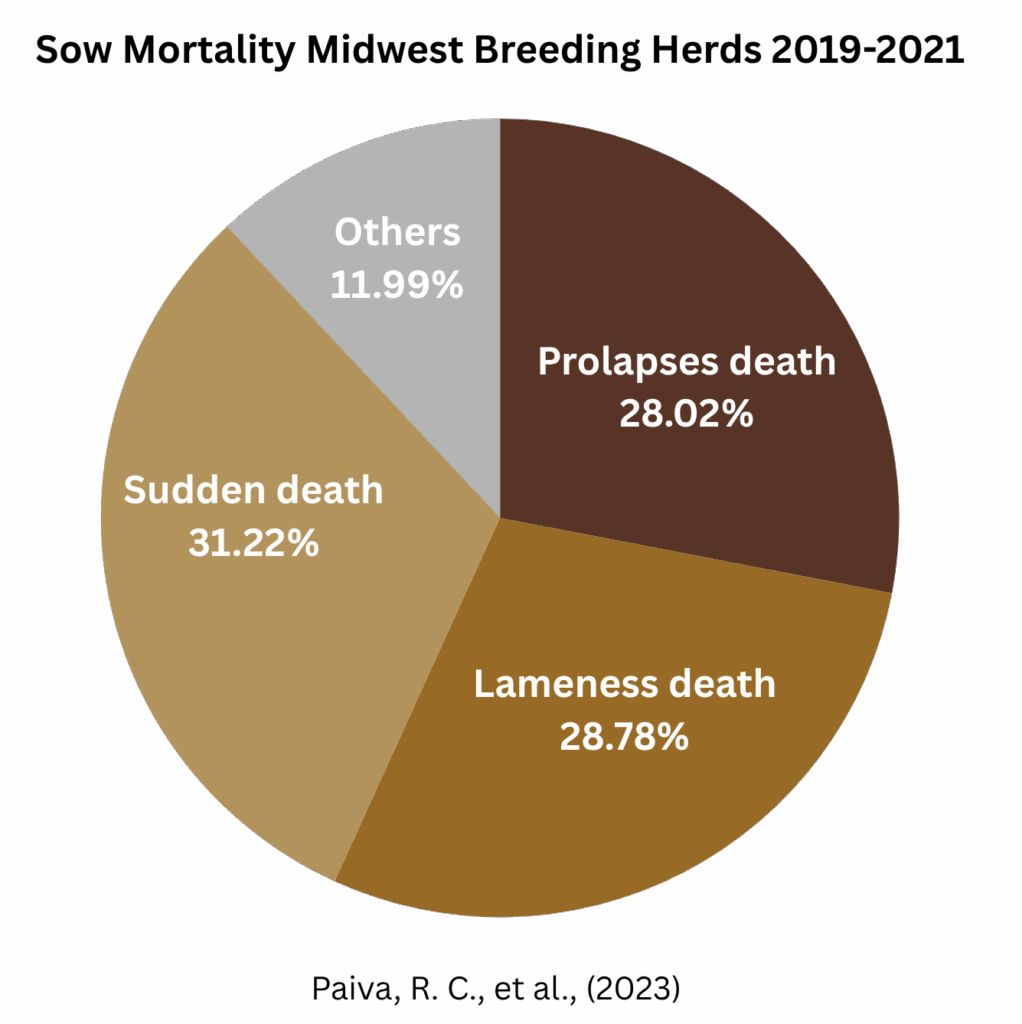

Prolapse – Pelvic organ prolapse is a condition where the uterine, vaginal, or rectal organs are displaced, often outside the body. It affects sows primarily around the time of giving birth. This brutal condition has increased significantly over the past decade, now responsible for about one-quarter of sow deaths.[7-9]

Farrowing Time – Larger litters have significantly lengthened the birthing time which increases stress and pain during parturition.[10,11] Longer farrowing has also been shown to increase the risk of birth complications and occurrence of post-partum diseases.[12]

Ward, S. A., et al., (2020), Are Larger Litters a Concern for Piglet Survival or An Effectively Manageable Trait? Animals, 10, 309, p. 3. [“As larger litters can impart greater stress and discomfort on sows, implementing a low-stress environment leading up to parturition may improve sow performance and subsequent survival of piglets.”]

Paiva, R. C., et al., (2023) Risk factors associated with sow mortality in breeding herds under one production system in the Midwestern United States. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 213, 105883, pp. 1-2. [“The causes of sow mortality may interact and vary over time, including management practices, nutrition, environment, and noninfectious and infectious factors.”]

Ross, J. W. (2019). Identification of putative factors contributing to pelvic organ prolapse in sows II. Iowa State Univ., Industry summary. [“At a farm level, the most apparent relationships with increased POP (pelvic organ prolapse) incidence were farms using untreated water sources and farms whose management strategies included late gestation bump feeding, particularly when targeting thin sows.”]

Chart data for years 2014-2024 [Bradley Eckberg (August 28, 2024) U.S. sow farm production update. National Hog Farmer (based on MetaFarms data)]

Data for 2004 from [PigCHAMP Knowledge Software, Benchmarking Summaries. Year-end summary 2004. Death rate of 7.87%. USA PigChamp data for 2023 = 14.73%]

Paiva, R. C., et al., (2023), p. 2.

Bradley Eckberg (Dec 13, 2023) U.S. sow mortality trends continue to climb, National Hog Farmer. [“As noted previously, 22.6% of all 2023 sow deaths losses occurred by way of prolapses.”]

Paiva, R. C., et al., (2023), Figure 2, p. 4. [At 28%, the rate of prolapse deaths was around that of death from lameness (28.78%) and “sudden death” (31.22%)]

Jason Ross (2019) Identification of putative factors contributing to pelvic organ prolapse in sows. Research Report Pork Checkoff, p. 8. [“POP (pelvic organ prolapse) was attributed to 21% of all mortality reported. The largest category was unknown/other including 39% of the total mortality. Lameness, at 29%, was the second largest category.”]

Peltoniemi, O., et al., (2020) Coping with large litters: the management of neonatal piglets and sow reproduction. J Anim Sci Technol, 63(1):1-15, p. 2. [“Based on 20 different studies carried out between 1990 and 2019, litter size has increased from ca. 10 to 20 piglets and farrowing duration has increased from 1.5–2 to 7–8 h.”]

Ward, S. A., et al., (2020), Are Larger Litters a Concern for Piglet Survival or An Effectively Manageable Trait? Animals, 10, 309, p. 3. [“Issues arise with larger litters as the farrowing process usually takes longer, which increases the risk of farrowing difficulties.”]

Oliviero, C., et al., (2019) The challenge of large litters on the immune system of the sow and the piglets. Reproduction in Domestic Animals, vol. 54, no. 53, p. 13. [“Parturition is known to be a painful process in large mammalian species and increasing its duration directly increases the suffering of the sow and stress of newborn piglets… In addition, this increment in the duration of the process of farrowing increases the risk of birth complications and occurrence of diseases post‐partum.”]

The primary causes are lameness, pelvic organ prolapse, and so-called “sudden death” – a catchall phrase for causes of death that in many cases are not sudden but rather are suddenly discovered.[1-3]

Of the ~6 million sows alive at a given point in time in the U.S., almost a million will die or be killed at the breeding facility each year due to health issues that prevent operators from sending them to the slaughterhouse.[4]

Paiva, R. C., et al., (2023) Risk factors associated with sow mortality in breeding herds under one production system in the Midwestern United States. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 213, 105883, p. 4. [Because of the many ways to categorize deaths on varying operations or in different studies, there is no single set of statistics that can be used. In general, it is understood that lameness is the largest cause at ~30%, and that pelvic organ prolapse is about a quarter of cases.]

Ross, J. W. (2019) Identification of putative factors contributing to pelvic organ prolapse in sows. Iowa State University, Figure 6, p. 8. [Lame, injured/downer = 29%; Pelvic organ prolapse = 21%; Unknown/other = 39%]

Kikuti, M., et al., (2023). Sow mortality in a pig production system in the midwestern USA: Reasons for removal and factors associated with increased mortality. Veterinary record, 192(7). [“Overall, the main reasons for death were locomotion (27%) and reproduction (24%).”]

USDA NASS (June 1, 2025) Quarterly Hogs and Pigs Inventory. [“Of the 75.1 million hogs and pigs, 69.2 million were market hogs, while 5.98 million were kept for breeding.” This is “a point in time estimate as of the reference date of swine inventory.” Likely less than 1% of the breeding hog inventory is made up of boars. 6M * .15 (sow mortality) = ~900,000]

The rate of piglet mortality increases when litter sizes grow, and it also increases with additional litters per sow (number of parities).[1-4]

The average rate of pre-wean mortality has increased in the last two decades. In 2004, the rate was 12.5%.[5] In 2024, PigChamp reported a rate of 14.2%.[6] The National Pork Board reported 16.4% for the same year and an end-of-year figure reaching 17%.[7,8]

The industry assesses “pre-wean mortality” as a share of piglets born alive, which excludes prenatal deaths like mummified piglets and stillborns, which have also increased with larger litters.[9]

Piglet mortality not only increases with litter size but also with the number of sow parities, suggesting that “the increase in litter size may have resulted in decreased piglet viability by stressing sows during gestation, which may raise the question for negative welfare consequences.”[10]

Andersen, I. L., et al., (2016) Maternal investment, sibling competition, and offspring survival with increasing litter size and parity in pigs (Sus scrofa). Behav Ecol Sociobiol, 65:1159, p. 1164. [“A positive relationship between litter size and piglet mortality is already documented.”]

Ward, S. A., et al., (2020), Are Larger Litters a Concern for Piglet Survival or An Effectively Manageable Trait? Animals, 10, 309. [“In turn, larger litters are strongly correlated with a proportion of piglets born underweight (<1.0 kg)… Thus, low-birth-weight pigs have an increased risk of pre-weaning mortality compared to normal-weight pigs.”]

Rahman, M. T., et al., (2023) Statistical and machine learning approaches to describe factors affecting preweaning mortality of piglets. Translational Animal Science, 7, txad117, Abstract. [“PWM (pre-wean mortality) increased with the increase of litter size, decrease in mean birth weight, increase in health diagnosis, longer gestation length, and at older parity.”]

Rahman, M. T., et al., (2023) p. 6 & 9, Table 5, p. 7. [“Mortality increases when the mean birth weight is low, and the litter size is large… It is important to note that litter size was highest in fourth parity, but this parity group also had the highest number of total dead piglets and stillborn piglets.” Piglet mortality rose to ~20% in 4th parities, versus 14% in first parities.]

PigCHAMP Knowledge Software, Benchmarking Summaries, USA 2004 year-end summary [pre-wean mortality rate = 12.47%]

PigCHAMP Knowledge Software, Benchmarking Summaries, North America 2024 year-end summary [For North America 2024, pre-wean mortality rate = 14.17%. For U.S. 2023, the figure was 14.6%]

National Pork Board, Meta Farms (2025) Production Analysis Summary for U.S. Pork Industry: 2020-2024, p. 3.

Nicole Beottger, MetaFarms (September 30, 2025) Benchmarking five-year trends in U.S. sow herds. National Hog Farmer. [“Pre-wean mortality ends at 17.0% in 2024…”]

The average number of stillborns per litter increased from 0.92 in 2004 to 1.16 in 2023. The average number of mummies per litter increased from 0.25 in 2004 to 0.56 in 2023 [PigCHAMP Knowledge Software, Benchmarking Summaries]

Rahman, M. T., et al., (2023), p. 8. [“Due to health effects for different parity levels, sows are more prone to have higher piglet mortality in higher parity order. Our finding that litter size increased with parity is consistent with previous studies.” Note: In this study, mortality in the 1st parity was 14.2% going up to 20.3% in the 4th parity. Litter size also increased with each parity. See, Table 5, p. 7]

There are many factors that contribute to pre-wean mortality. Most researchers agree, however, that increased litter size is directly associated with piglets born with low birth weights which predisposes them to injury and/or death.[1-4] The major risks – all connected to low birth weights:

Crushing – Low birth-weight piglets will stay longer near the sow’s udder (for milk and heat) and are at greater risk of being crushed.[5] Crushing is the number one direct cause of pre-weaning mortality.[6,7]

Chilling/ Hypothermia – Low weight piglets have less ability to maintain body temperature, and the resulting hypothermia affects their ability to suckle and ultimately to survive.[8] “Commercial production facilities often operate with suboptimal environments for piglets, with draughts, skin wetness and cold flooring being contributing factors to pre-wean mortality.”[9]

Starvation – Small and/or chilled piglets are less able to compete at the sow’s udder, leading to lethargy and starvation.[10] Competition for teat access grows with larger litters, while functional teat numbers are still relatively fixed at about 14 per sow.[11-13]

The majority of pre-wean mortality occurs in the first 72 hours of life. “However, piglets are at additional long-term risk from disease if they have failed to acquire sufficient immunity from colostrum as a result of delayed or limited suckling in the immediate post-natal period.”[14]

See generally, Rutherford, K.D.M., et al., (2013) The welfare implications of large litter size in the domestic pig I: biological factors. Animal Welfare Journal, vol. 22, no. 2.

Ellis, M., et al., (2019) 56 Observations on pre-weaning piglet mortality. J. Anim Sci, Vol 97, Issue Supplement 2. [“Genetic improvements in prolificacy have been accompanied with lower average piglet birth weights, increased within-litter variation in birth weight, and an increasing proportion of low birth weight piglets. Low birth weight is a major predisposing factor for PWM (pre-wean mortality).”]

Muns, R., et al., (2016) Non-infectious causes of pre-weaning mortality in piglets. Livestock Science 184, 46-57, p. 48. [“Many studies have reported that piglet birth BW is the most important factor for survival and performance.”]

Ward, S. A., et al., (2020), Are Larger Litters a Concern for Piglet Survival or An Effectively Manageable Trait? Animals, 10, 309, p. 2. [““Once the uterus has surpassed normal limits of uterine space, every additional littermate is associated with a reduction in individual fetal growth. In turn, larger litters are strongly correlated with a proportion of piglets born underweight…and they are more susceptible to weakness, hypothermia and hypoglycemia within the first 24 h of life.”]

Rutherford, K.D.M., et al., (2013), p. 201. [“For LBW piglets, the risk of crushing is increased because they spend longer near the sow’s udder. Thus, it is possible that a vulnerable neonate may experience chilling, starvation and then crushing, which highlights the considerable welfare issues surrounding piglet mortality.”]

USDA APHIS (2015), Swine 2012, Part I: Baseline Reference of Swine Health and Management in the United States, 2012, p. 48. [Crushing by sow causes 49% of pre-weaning deaths.]

Nicolaisen, T., et al, (2019) The Effect of Sows’ and Piglets’ Behaviour on Piglet Crushing Patterns in Two Different Farrowing Pen Systems. Animals, 9, 538, p. 2 & Table 1. [“These piglets are highly susceptible to hypothermia, starvation and, subsequently, to crushing, which is the main cause of pre-weaning piglet mortality in intensive pig husbandry.” At 36% in farrowing crates in German study.]

Muns, R., et al., (2016), p. 48. [“Body weight strongly influences an important piglet survival indicator– thermoregulation ability. Within the first hours after birth, thermoregulation is compromised in piglets because of evaporation of the placental fluids and consequent cooling. Susceptible piglets fail to recover from this initial temperature drop, and hypothermia affects the latency to suckle, leading to starvation, lethargy and, ultimately, to crushing by the sow.”]

Tucker, B. S., et al., (2021) Piglet Viability: A Review of Identification and Pre-Weaning Management Strategies. Animals, 11, 2902, p. 4.

Muns, R., et al., (2016), p. 48.

Earnhardt-San, A. L., et al., (2023). Genetic parameter estimates for teat and mammary traits in commercial sows. Animals, 13(15), 2400. Abstract [Functioning teats = 13.90]

Wiegert, J. G., & Knauer, M. T. (2018). Sow Functional Teat Number Impacts Colostrum Intake and Piglet Throughput. Journal of Animal Science, 96 (suppl_2), 51-52. [Average functional teat number was 14.83]

The Pig Site (November 9, 2018) The Udder. [“The ideal would be 16 teats, but this may represent only 5% of the gilt population, with around only 25% having 14 – so the commercial choice is 12 good teats with 14 or 16 in the Meishan cross breed. If however, you are selecting gilts from your own herd, select 14 or more if possible.”]

Rutherford, K.D.M., et al., (2013), p. 201.