The beef industry and its supporters have kept alive the notion that there is some controversy about whether grazing cattle in America is beneficial for the land. This is despite clear evidence that grazing has degraded land conditions across the nation and that climate change and drought are steadily increasing the toll.

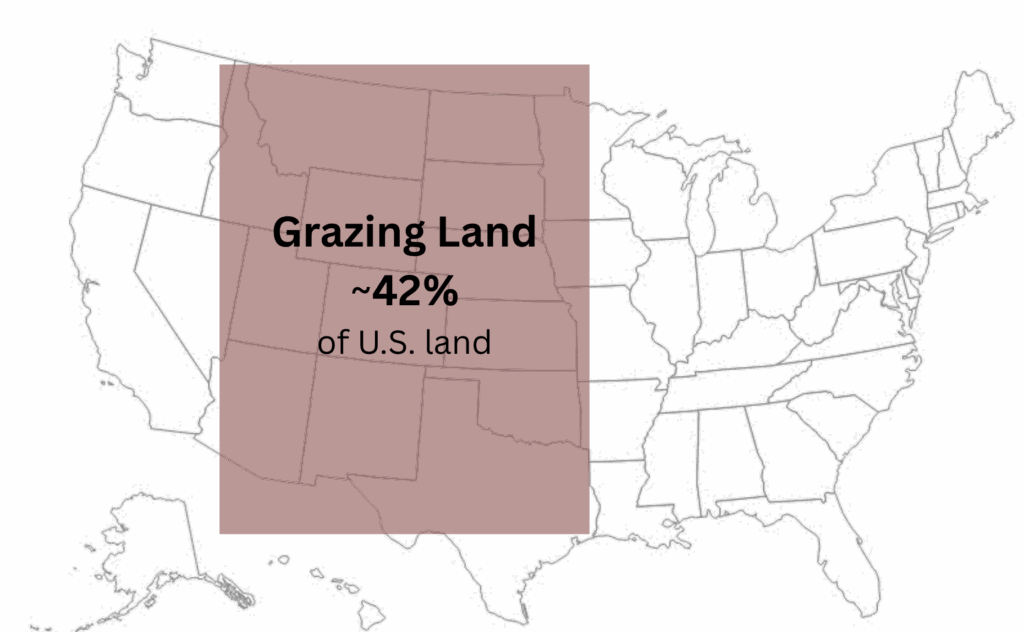

It’s a critical subject since grazing is by far the largest use of land, currently on more than 42% of the contiguous U.S. The web of grazing operations across 800 million acres is the pipeline into massive factory farm feedlots.

It’s a critical subject since grazing is by far the largest use of land, currently on more than 42% of the contiguous U.S. The web of grazing operations across 800 million acres is the pipeline into massive factory farm feedlots.

The term “land degradation” is understood to mean the deterioration of soil and water resources and the loss of biodiversity. Globally, grazing is considered the primary driver of land degradation. There is no indication that U.S. grazing practices, land conditions, and climate would produce a different result.

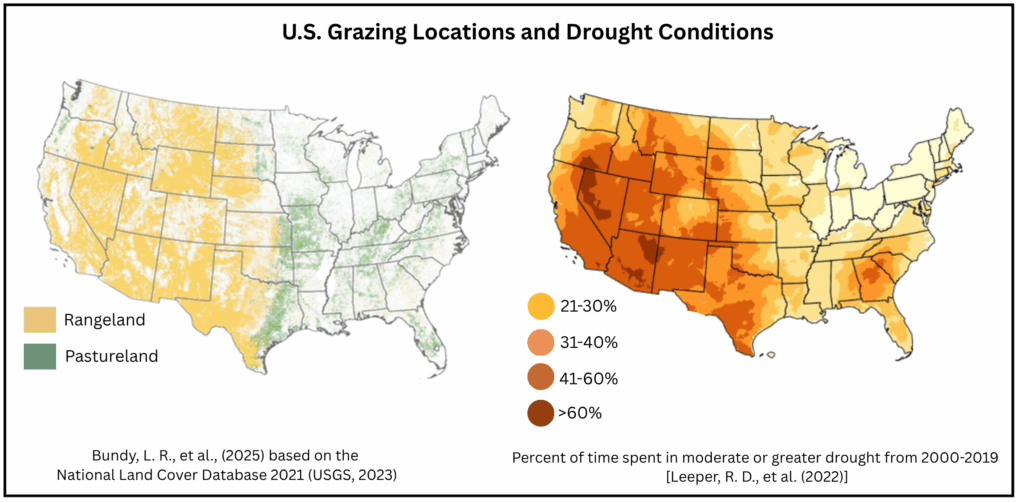

In fact, the opposite is true. Drylands are the grazing areas most susceptible to degradation. These are semi-arid and arid regions where low rainfall limits plant growth. The great majority of grazing lands in the U.S. are western drylands, where it is widely acknowledged, including by federal agencies, that climate change, increasing droughts, wildfires, and invasive species are taking a severe and accelerating toll. The past two decades have been the driest in the West in the last 1,200 years.

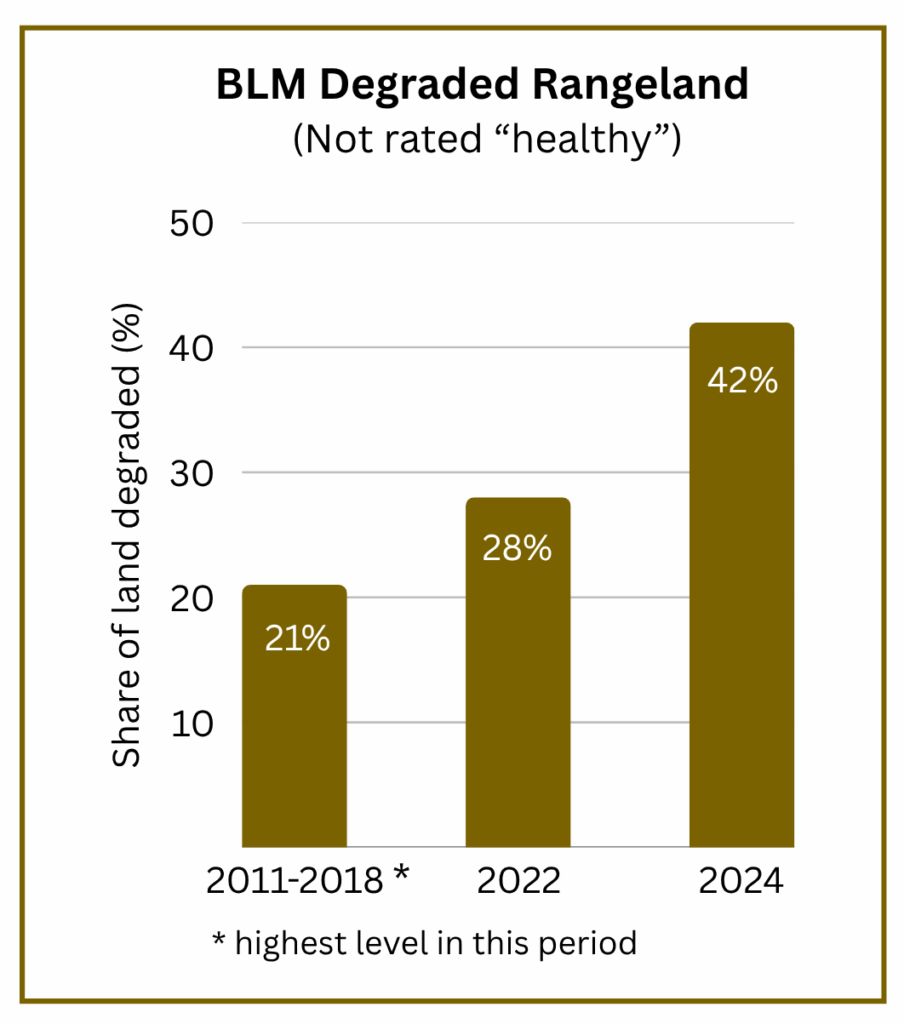

The two agencies that regularly evaluate grazing conditions, the USDA and the BLM, have documented the steady degradation of grazing land conditions across the country. A fair reading of U.S. agency reports leads to a conclusion that between a quarter and a half of federal and private grazing lands are degraded, with the share steadily increasing.

Given these facts, how has the beef industry managed to keep the “debate” alive? We all know the playbook whereby tobacco and fossil fuel companies sowed enough disinformation to create uncertainties about smoking and climate change. The resulting “controversy” offers cover to those who have difficulty giving up damaging habits that are profitable for industry.

But with grazing there’s more to the story. The cattle industry is deeply entwined with the history, traditions, and economics of this country. Out west, as Cliven Bundy showed us, many are willing to die on the hill of grazing rights, illegal or not. The cowboy on the open range is the classic American icon associated with personal freedoms. Beef consumption is considered by many to be a non-negotiable expression of that freedom, as is the dominance over nature.

But with grazing there’s more to the story. The cattle industry is deeply entwined with the history, traditions, and economics of this country. Out west, as Cliven Bundy showed us, many are willing to die on the hill of grazing rights, illegal or not. The cowboy on the open range is the classic American icon associated with personal freedoms. Beef consumption is considered by many to be a non-negotiable expression of that freedom, as is the dominance over nature.

Unfortunately, our federal agencies have enabled the ongoing losses. They hide their own land condition evaluations, burying the lede in long reports with obscure language. Evidence of land degradation is typically referred to as “resource concerns” or the more inscrutable “departure from reference conditions.” Although the USDA has for decades generated reports on weekly grazing conditions around the country, it downplays the troubling trends.

There is no federal agency looking at the full extent of damages. Naturally, the USDA is focused on the land’s capability to produce agricultural products, so the availability of forage is their key metric rather than, for example, tracking grazing’s impacts on native animal species. At the BLM, one enforcement officer covers more than a million acres, and he or she may be more worried about surviving a faceoff with an angry rancher than assessing meager fines on unauthorized grazing – the extent of which is essentially unknown.

The idea that regenerative grazing is a practical solution would be ludicrous but for the amount of attention it gets in research papers. There are several hundred thousand cattle operations in the U.S., each operating under site-specific, complex, and often deteriorating conditions. Many ranchers feel intense economic pressure, and a large portion operate on rented land. Even assuming an interest in conservation, there is no one-size-fits-all methodology that can be widely implemented or monitored.

The idea that regenerative grazing is a practical solution would be ludicrous but for the amount of attention it gets in research papers. There are several hundred thousand cattle operations in the U.S., each operating under site-specific, complex, and often deteriorating conditions. Many ranchers feel intense economic pressure, and a large portion operate on rented land. Even assuming an interest in conservation, there is no one-size-fits-all methodology that can be widely implemented or monitored.

More critically, the economics don’t work. Domestic beef products from so-called “grass-fed” beef make up about 1% of the U.S. beef market, at more than double the cost to consumers. Product from credible regenerative systems is likely an even smaller share. And yet, the idea that somewhere, somehow, there are operations using these practices to mend the land has seemingly offered to all beef consumers the guilt assuaging notion that “grazing is good.”

This obfuscation is a temporary reprieve for the U.S. beef industry. Land conditions are worsening, and the weather forecast out west calls for hot and dry. The curtain will inevitably be pulled back on the damage to soils, streams, and plant and animal communities. Like tobacco and fossil fuels, grazing is good – until it’s not.

For more info and references see:

Land Degradation & Grazing

Grazing on Federal Lands